Tags

astronomy, exoplanets, life, nasa, National Capital Astronomers, NCA, Rob Zellem, science, solar systems, space, UMCP, Universe, University of Maryland

Dr Rob Zellem posed this question last night (9-13-2025) to NCA members and visitors at their monthly meeting at the University of Maryland Observatory.

Are we alone in the universe, or are there exoplanets with life of some sort, and even some advanced civilizations out there?

Dr Zellem said the correct answer right now is, maybe. We just don’t have enough data to tell.

He reminded us that Giordano Bruno and Isaac Newton both correctly predicted that other stars would have planets around them. We now know that just about every single star is born with a retinue of planets, asteroids, dust, and comets, so there are at least as many planets as there are stars in our galaxy and all the others as well. Previous speakers to NCA have noted that many of these objects end up getting flung out into the vast frozen emptiness of interstellar space in a giant random game of ‘crack the whip’. No life can exist out there.

My calculations here: It is estimated that there are literally trillions (10^12) of galaxies, each with millions (10^6) or billions (10^9) of stars. Let’s start with our own galaxy, the Milky Way, with maybe 200 billion stars (maybe more). I will assume that life needs a nice, calm, long-lived G class yellow star, which only make up 7.6% of all stars. Roughly 50% to 70% of those stars are in binary systems, which I fear will reduce the chances of having a planet survive in the Goldilocks zone. Perhaps one-third to two-thirds of those G stars have a planet in their habitable zone. We have no idea how likely life is to get started, but after reading Nick Lane’s The Vital Question it sounds pretty complicated to me, so I’ll use a range of estimates: somewhere between 10% and 80% of them develop some form of life. We know that on Earth, the only form of life that existed during the vast majority of the existence of the Earth was unicellular microbes. Four-footed tetrapods like ourselves have only occupied about 1% of the life of our planet, and we humans have only had the telescope for just over 400 years, out of the 400,000,000 years since four-footed animals evolved, which is one in a million. Low estimate:

If my low-end estimates are correct, then there are about five or so exo-planets somewhere in our galaxy with a civilization formed by some sort of animal that can look out into outer space. High estimate:

In that case, there are well over a hundred civilizations in our galaxy — but the Milky Way is huge, hundreds of thousands of light-years across! Most of our exoplanet detections have been within the nearest 100 light years, and we have no way of detecting most exoplanets at all because the planes of their orbits point the wrong way.

NOTE: Jim Kaiser pointed out that I made a dumb mistake: a hundred billion is ten to the 11th power, not ten to the 14th power. Fixed now.

Even so, Zellem pointed out that thanks to incredible advances in sensitivity of telescopes and cameras, we are now closer than ever to being able to answer the title question: Are We Alone.

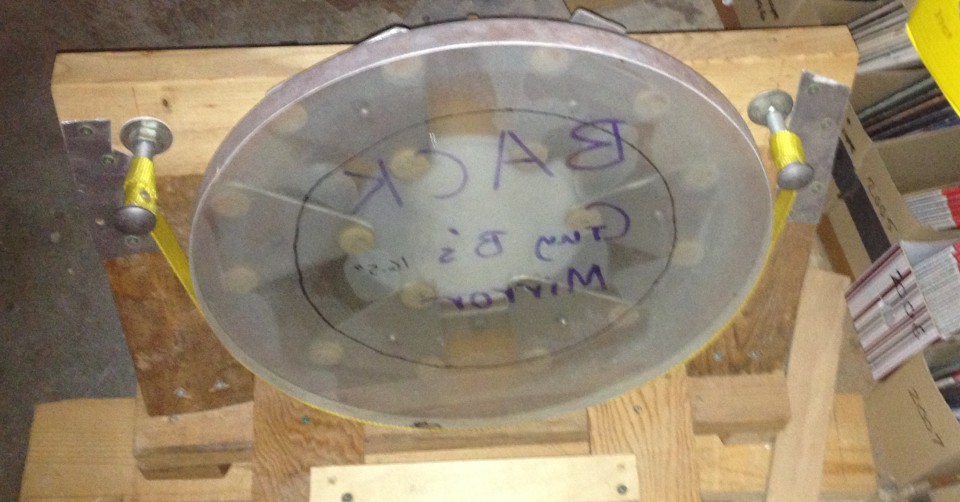

Plus, any amateur astronomer can take useful measurements of exoplanet transits with any telescope, and any digital camera. Following the directions on NASA’s Planet Watch webpage, you can take your data, in your back yard or from a remote observatory, process it the best you can, send it in, and be credited as a co-author on any papers that are published about that particular exoplanet. Then, later, a massive space telescope can be aimed at the most promising exoplanets during their transits. Astronomers can use their extremely sensitive spectroscopes to detect the atmospheres of those bodies and look for signs of life. They do not want to waste extremely valuable telescope time waiting for a transit that doesn’t recur!

Some day we will be in a situation where scientists will be able to say that based on their measurements, the signal indicates a very good chance of life at least a bit like ours, with similar chemistry on some planet. They will also state what the chances are that they are wrong, and indicate what further steps could be made to disprove or confirm their claim.

Zellem noted that both the Doppler-shift method and the transit methods are quite biased in favor of large exoplanets that are close to their suns.

I asked the speaker how likely it would be for observers from some exoplanet to detect the planet Mercury, but couldn’t do the math in my head and didn’t have paper and pencil to write anything down at the time. But now I do.

The closer Mercury is to the Sun, the larger the possible viewing angle.

Using a calculator to find the arc-tangent of that ratio (865,000 miles solar diameter, divided by the smallest and also by the largest distances between them, namely 28,500,000 and 43,500,000 miles) gave me an angle between 2 and 3 degrees, depending. So there is a circular wedge of our galaxy where observers on some other planet might view a transit of our innermost planet. Where is that wedge in our galaxy?

The following sky diagram has the Ecliptic in pink. Only observers within a degree or so of that curvy line could detect that Sol has planets.

So what fraction of the sky can ever hope to catch a transit of Mercury? Only about 1% or 2% of the sky — not much.

Turning things around, this means that we can ourselves only detect, via transits, a very small portion of all extra-solar planetary systems – those whose planes are pointing almost directly at us, and those with large planets that are very close to their stars. (Any planet so close to a star is not a very good candidate for life, in my opinion.)

The biggest obstacle is the sheer distances between stars. At the speed of our very fastest space craft (the Parker Solar Probe), which only goes 0.064% of the speed of light, it would take about 6250 years to reach our closest stellar neighbors near Proxima Centauri. One way. Which probably explains why, if all these other civilizations do exist, we do not appear so far to have been visited by any other extraterrestrial civilization.

At the meeting, someone in the audience was pretty sure that yes, we have already been visited by aliens. I talked with him outside after the meeting. His main evidence was a 2020 New York Times article concerning the upcoming release of classified data about mysterious flying objects (now called UAPs rather than UFOs). In the article, one Eric Davis claimed (without producing any evidence) that some items have been retrieved from various places by the US military that couldn’t be made here on earth. That is of course true of every single asteroid or meteorite ever discovered, since we can’t reproduce the conditions in which they were formed, so his claim is not very helpful. No technological devices clearly of alien manufacture have ever been publicly produced by him or anybody else for testing.

(It’s pretty obvious that American and other military forces spend a lot of money producing objects that go very fast and are highly maneuverable — and which they want to keep secret.)

There are in fact many, many unsolved mysteries in science (eg, the nature of dark matter and dark energy, and exactly how the nucleus arose in eukaryotes). Many of the unidentified sky or water phenomena that have been witnessed do not have clear explanations so far, but the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. Reputable scientists require a lot more than hearsay evidence before they make bold claims.

Thank you for a great talk, Rob Zellem!