We at the Hopewell Observatory have had a classical 12″ Cassegrain optical tube and optics that were manufactured about 50 years ago.; They were originally mounted on an Ealing mount for the University of Maryland, but UMd at some point discarded it, and the whole setup eventually made its way to us (long before my time with the observatory).

The optics were seen by my predecessors as being very disappointing. At one point, a cardboard mask was made to reduce the optics to about a 10″ diameter, but that apparently didn’t help much. The OTA was replaced with an orange-tube Celestron 14″ Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope on the same extremely-beefy Ealing mount, and it all works reasonably well.

Recently, I was asked to check out the optics on this original classical Cassegrain telescope, which is supposed to have a parabolic primary and a hyperbolic secondary. I did Ronchi testing, Couder-Foucault zonal testing, and double-pass autocollimation testing, and I found that the primary is way over-corrected, veering into hyperbolic territory. In fact, Figure XP claims that the conic section of best fit has a Schwartzschild constant of about -1.1, but if it is supposed to be parabolic, then it has a wavefront error of about 5/9, which is not good at all.

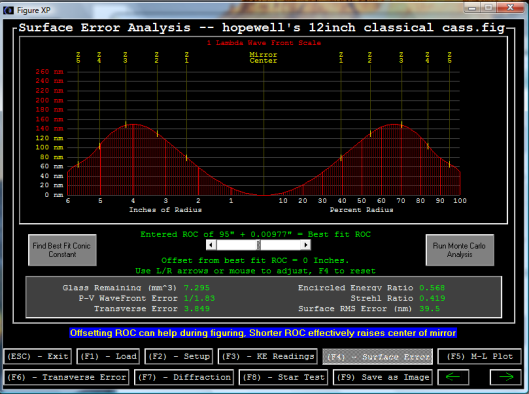

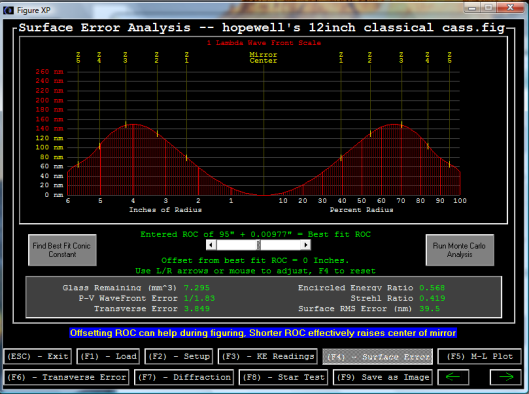

Here are the results of the testing, if you care to look. The first graph was produced by a program called FigureXP from my six sets of readings:

I have not yet tested the secondary or been successful at running a test of the whole telescope with an artificial star. For the indoor star test, it appears that it only comes to a focus maybe a meter or two behind the primary! Unfortunately, the Chevy Chase Community Center where we have our workshop closes up tight by 10 pm on weekdays and the staff starts reminding us of that at about 9:15 pm. Setting up the entire indoor star-testing rig, which involves both red and green lasers bouncing off known optical flat mirrors seven times across a 60-foot-long room in order to get sufficient separation for a valid star test, and moving two very heavy tables into said room, and then putting it all away when we are done, because all sorts of other activities take place in that room. So we ran out of time on Tuesday the 5th.

A couple of people (including Michael Chesnes and Dave Groski) have suggested that this might not be a ‘classical Cassegrain’ – which is a telescope that has a concave, parabolic primary mirror and a convex, hyperbolic secondary. Instead, it might be intended to be a Ritchey-Chretien, which has both mirrors hyperbolic. We have not tried removing the secondary yet, and testing it involves finding a known spherical mirror and cutting a hole in its center, and aligning both mirrors so that the hyperboloid and the sphere have the exact same center. (You may recall that hyperboloids have two focal points, much like ellipses do.)

Here is a diagram and explanation of that test, by Vladimir Sacek at http://www.telescope-optics.net/hindle_sphere_test.htm

FIGURE 56: The Hindle sphere test setup: light source is at the far focus (FF) of the convex surface of the radius of curvature RC and eccentricity ε, and Hindle sphere center of curvature coincides with its near focus (NF). Far focus is at a distance A=RC/(1-ε) from convex surface, and the radius of curvature (RS) of the Hindle sphere is a sum of the mirror separation and near focus (NF) distance (absolute values), with the latter given by B=RC/(1+ε). Thus, the mirrorseparation equals RS-B. The only requirement for the sphere radius of curvature RS is to be sufficiently smaller than the sum of near and far focus distance to make the final focus accessible. Needed minimum sphere diameter is larger than the effective test surface diameter by a factor of RS/B. Clearly, Hindle test is limited to surfaces with usable far focus, which eliminates sphere (ε=0, near and far focus coinciding), prolate ellipsoids (1>ε>0, near and far foci on the same, concave side of the surface), paraboloid (ε=1, far focus at infinity) and hyperboloids close enough to a paraboloid to result in an impractically distant far focus.

We discovered that the telescope had a very interesting DC motor – cum – potentiometer assembly to help in moving the secondary mirror in and out, for focusing and such. We know that it’s a 12-volt DC motor, but have not yet had luck tracking down any specifications on that motor from the company that is the legatee of the original manufacturer.

Here are some images of that part: