Practical Details on the Shaping of Glass Mirrors and Performing Local Refiguring

When the glass mirror is not too large, say, not more than 20 cm across, then work on the surface does not present any difficulty to speak of, and we can simply continue to use the methods employed in any optical workshop. We begin by preparing a pair of copper basins a little larger than the glass. Then we give them the desired surface curvature, and we bring them together, in sort of a mortar-and-pestle [balle et bassin in the original – trans.] fashion, one inside the other, by rubbing one against the other with finer and finer grades of emery abrasive. The glass is then placed on its back, roughed out, its edges are chamfered, and we rub it with emery and water on the convex copper basin, until the entire surface has acquired a very fine and uniform haze.

.

Then we glue onto the previously-mentioned convex copper tool (or “ball”) a sheet of paper which we impregnate with English rouge. By a prolonged rubbing on this polishing lap, we can clear up the surface of the glass, which after a while obtains a perfect polish. By working in this manner, a skilled operator can produce a surface of revolution which does not coincide exactly with a sphere, but differs from it in a direction that is favorable for correction of spherical aberration. Such a mirror may have an opening that is wider than that which corresponds to an exact spherical figure.

.

But when we begin to work on larger diameters, we cannot depend on such an empirical correction to be exact enough, so it is necessary to turn to local refiguring. Also, the price of the copper basins rises very rapidly as the size increases; their weight becomes quite heavy, and the increasing friction between the glass and the metal renders the work painfully difficult and diminishes the chances for success. Because of these various reasons, we have given up using metal tools, and have turned to working glass mirrors against glass tools. Henceforth, the cost of setting up shop merely consists in acquiring two disks of glass of the size and shape appropriate to the desired finished product.

.

For example, if we plan on constructing a mirror of 40 to 50 cm in diameter, we begin by procuring, by melting them and casting them in a mold, two disks of thick and well-annealed glass, each one with a convex obverse side. The next step is to rough them out by mechanical means so that the two surfaces have approximately the desired degree of curvature. We stroke the two disks in a in a circular fashion with the upper one, the tool, moving past the edges of the other one. We polish the obverse side of the other disk, and on the peripheral edge of each one we carve a groove which will be used to attach the cords that will aid in the work.

.

The two pieces of glass thus prepared, mirror and tool, are then taken to the optician’s workshop and entrusted to a skilled worker, so as to be worked one against the other with all the skill needed to produce a surface of revolution. The work proceeds upon a solidly established post, a sort of pillar isolated on all sides, which bears on its center a threaded screw on which is mounted a knob or chuck which we attach to the back of both disks with pitch. Directly above this work-post, we attach to the ceiling a strong crew-hook from which we hang a helical spring that is able to support the weight of the mirror. Finally, in order to make it easier to grip the work and move it about, we screw onto the post an appendix, with a large and jutting-out border. This will serve , if needed, as a point of attachment for the cords, more-or-less taught, that will attach to the suspension spring.

.

The glass tool being attached to the post, we spread on its surface some medium coarse abrasive, wetted with some water. We carefully place the mirror on top of it, and we rub the two pieces one against the other, taking care to vary the movements of the glass in such a way as to distribute the action equally in all directions. At the same time that he moves around the post, the worker causes to rotate under his hand the edge of the knob in such a way that the tool and the mirror will have positions that are constantly changing with respect to each other.

.

Bit by bit, the abrasive is worn down, and to prevent it from drying out, we wet it constantly by sprinkling drops of water onto the parts of the glass that in their turn become exposed to view. As the work continues, the abrasive loses its cutting power, becomes finer and finer, and also becomes mixed with particles of glass removed from both disks. After a while, the worker notices that it is advisable to take the upper disk off, sponge both of them off to clean them, and to start over with new abrasive.

.

There is a certain art in learning how to work well with the abrasive in such a way as to distribute the emery evenly between the two surfaces, and to keep it moist enough and during a time long enough so that it can work most effectively. In unskilled hands, the abrasive is not spread out well, does not work at the glass correctly, and escapes out the sides without having performed all its duties. If that is the case, one wastes one’s time in false maneuvers, one uses excessive amounts of abrasive, and the work does not advance.

.

The first grades of grit are designed to make the two surfaces adapt to each other. We know that result has been achieved when both pieces of glass move against each other in all directions without any preference. We then use finer and finer grades of abrasive, which are denoted in the trade by the number of minutes that they take to separate out of suspension when one mixes them up with water. These abrasives of one, two, … forty, and sixty minutes are used in succession between the two surfaces, until they eventually give to the blank a velvety and uniform grain whose fine quality appears to have a semi-transparent and opaline luster.

.

If we want to obtain a surface with a certain specified radius, then it is advisable, during this long succession of different grades of abrasives, to employ from time to time a spherometer. In case we need to increase the radius of curvature, all we have to do is to attach the mirror to the post and to continue working with the tool on top. In the opposite case, simply leave the arrangement as it was to begin with, i.e. mirror on top, and to move the mirror with longer strokes.

.

These two methods of modifying the radius of curvature work very well, especially when one works glass-on-glass. We can understand why this is so when we consider that as soon as one of the disks passes beyond the edge of the other, the piece that is on top presses its central section upon the edge of the other. It therefore follows that the grinding action, instead of being distributed uniformly, takes place for the most part on the periphery of the lower piece and on the central part of the upper piece. One needs no more than this to explain why this unequal division of pressure and wearing away tends to increase the curvature of the glass, in the case that the concave piece is on top, and to decrease it when the positions are reversed. When we realize how to take this factor into account, not only do we no longer have to fear its effects, but we can also use it to maintain any desired radius of curvature right up to the moment when we start polishing.

.

With the surface haze brought to a high degree of fineness, we now need to bring it to a perfect polish. We are acquainted with several methods for polishing glass, but the one that appears to us to be the best for working on mirrors is the method of polishing with paper laps (the opthalomatic polishing pads of today are the derivative of this method – Bob) and English rouge. On the very surface of the disk which served as tool for the mirror, we use starch [pitch? gfb] to glue a piece of paper whose weft appears as uniform as possible. By using a sort of glass meniscus known as a “colloir”, we push the excess starch [pitch? gfb] towards the edges of the glass, and we apply the paper completely and fully onto the tool surface. Then, by rubbing the glass with a damp sponge, we detach the little particles of paper, and we strip or roughen the paper in such a way as to raise a velvet-like nap which, once dried, will be effective at holding the polishing powder. We must still rub the paper with pumice, then chase it with a brush, after which we apply the English rouge with a scrap of crumpled paper. Now the polishing lap is ready.

.

The mirror, having been washed and dried, is placed on this lap, which touches it all over and will make the finish clear up after the very first few strokes. But before putting the mirror into motion, it is necessary to support a pat of its weight by attaching it again to the suspension spring and by using a cord that is stretched sufficiently tight. This arrangement also has the benefit of allowing us to move a rather large mass without too much effort. But what is more important is that by reducing the pressure upon the polishing lap, we slow down the creation of heat due to the friction of polishing, and we avoid to a certain extent the deformations that would result from that heat.

.

If, however, we neglected this precaution, then the heat generated by energetic strokes would make both of the pieces expand, and they would cease to be in contact with each other at their edges and would only touch near their center. In this case, the mirror would pivot on its center, only the central portion would become polished and would become dug-out, and the edges would remain hazy. But, by using the spring, we establish a more equal action. Even though the polishing may take a bit longer, we are ever more assured of a good result.

.

When the mirror seems to be entirely polished, we perform a preliminary test, and if the surface does not present any serious imperfections, we undertake to lead it towards the necessary figure for a perfect objective mirror by means of local retouching methods.

.

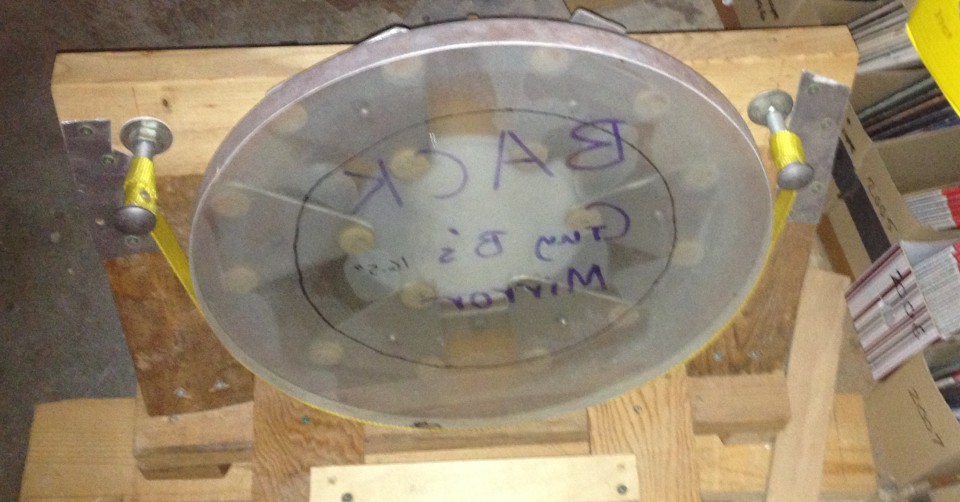

In order to perform this delicate operation in a suitable manner, one needs to have available an enclosed space where one can set up an optical testing line about four or five times as long as the focal length of the mirror. At one end, we set up the mirror in a frame that will fit into the tube of the telescope. This tube, with its prism and eyepieces removed, is carried on two trestles or sawhorses that hold it in a horizontal position and raise it to a convenient level for observations. Tables to hold the objects needed for the mirror tests can be placed all along the observation line. In addition, on a separate structure like an optician’s work-post, we set up, to receive the mirror, a wooden basin whose curvature matches the back side of the glass.

.

Finally we prepare, for the purpose of local refiguring, a series of polishing laps whose diameters vary from about a fifth to a third of the piece that is being figured. These polishing laps are made of glass covered with paper and mounted on handles made out of wood or cork. They are used to work certain determined zones of the mirror surface and to wear them down in the same way as we produced the overall polishing of the surface. But, in order that this removal of material operates without breaking the continuity of the mirror’s curvature, or, in other words, so that this refiguring takes place without creating a discontinuity or a noticeable line of demarcation with the original surface, it is absolutely necessary to prepare the polishing tools with the utmost care. For this reason, we believe it is useful to describe practical details and very precise information on this subject.

.

From our very first attempts, we learned that the best curve to give to the local refiguring laps was not one that exactly coincided with the curvature of the mirror: it is better to give it a small excess of convexity, because that way, the lap will contact at its center. Consequently, the refiguring will more directly address the section which one plans to work on, and it will flow into the surface on one side and the other of the point of contact in a way that is not noticeable. However, one should not exaggerate this excess of convexity in the tool, because if one does, the contact between the lap and the mirror would be restricted to an area which would no longer correspond to the area of the polisher. Finally, even if the lap has the desired curvature, it is important to pay close attention to the state of the paper which carries the polishing powder, because sometimes it happens that the rouge will move around, and when doing so, they will leave the center point of contact in such a way as to foul up the operation and to hamper the refiguring. Thus, there are several delicate conditions that must be maintained. But the art of the optician offers resources which permit us to overcome all these difficulties.

.

When one wants to prepare a polishing lap and to imbue it with the precise curvature needed for refiguring work, the way to do it consists of “marrying” it to a counterpart made of glass with the same diameter and the opposite curvature. Thus one has, so to speak, a mortar and pestle which one works one against the other with all the care that one would bring to the execution of a really fine surface. Once these disks have been matched against each other, it is necessary to check the curvature. For this we place the concave part on the main tool which we used for working the mirror, and whose surface has remained unpolished. By a rubbing in place we make appear a whitish line which reveals the distribution of the points of contact. For the convex polishing lap to end up touching the mirror at its center, it is obvious that it is necessary that the little concave “basin” must touch the large “ball” on its edges and to leave upon it an annular path when rubbing. As long as this result has not been obtained, we continue to modify the curvature of the laps by rubbing them against each other, taking care that the “basin” is either above or below, depending on whether we need to increase or decrease its curvature. Finally, when the check performed by rubbing the lap onto the haze of the large “ball” gives a ring-like trace which dies out about halfway to the center, we are then sure that the two disks have the desired curvature, and we can begin gluing the paper on them.

.

In the last resort, it could be sufficient to simply top off the paper of the polishing lap in the usual way. But just as the two pieces of glass have been used to prepare each other by rubbing glass against glass, in the same way we finish both of the laps by having undergo a similar treatment, paper against paper. We use starch to glue the papers, using the meniscus to eliminate the excess glue; we rub a wet sponge lightly all over the glass, taking care to lightly attack the “skin” formed by the original gluing; and we let it all dry out. When the humidity has dissipated, we find the paper to be well-stretched, but since it is rough and covered with little ball-like particles that were detached by the sponge, we remove them by rubbing it with a flat pumice stone, and we then chase them off with a brush. In this state, we could consider the polishing lap to be ready to go into action. However, since the paper may vary in thickness from point to point, we make it undergo a final preparation which has the effect of raising a velvet-like nap that is very good at holding rouge. This preparation consists of bringing the two papers together, working one against the other with powdered pumice that is wetted with a liquid which will not dissolve the starch. To do this, we place the polishing lap on the work post, wet it with benzene, dust it with pulverized pumice, place the “basin” on top, and we perform motions for a while as if we were doing fine grinding. Bit by bit the benzene evaporates, the pumice which had formed a sort of soup becomes once again a powder, and when we feel that the two pieces are beginning to stick together, we remove the “basin,” and we repeat the whole operation two or three times.

.

To finish it all up, we brush both surfaces carefully and for an extended period of time, and we see the paper once again become white. But if we look at it carefully, we notice that the surface has changed for the better, in becoming covered with a uniform velvety nap whose presence always helps the action of the polishing lap.

.

As to the manner in which we spread and fix either the rouge or the diatomaceous earth [“tripoli de Venise” – gfbl.] which gives it a bit more bite, we have noticed that the treatment with pumice and benzene produces a uniformity that is seldom found in a sheet of paper used “as is.” When the work continues for a long time, for example if a polishing lap has been worked for several hours, we see it behave quite differently depending on whether or not it underwent the last preparation mentioned above. When one omits bringing the two paper-covered laps together, it is true that the operation will work well for a while; but soon, in the central region where the most pressure is felt, the paper begins to wear, to lose its porosity, and peels off its surface layer. It becomes shiny and no longer holds the powders, which flee to the edges. In such a case, despite the excess of convex curvature of the polishing lap, its action no longer takes place in the center, but on the edges. Therefore, instead of light refiguring taking place which flows imperceptibly from area to the next, we run the risk of plowing relatively deep furrows that are very difficult to repair.

.

If, on the other hand, we had taken care to rub the polisher via the procedure described earlier, the rouge would lodge more permanently in the paper, so that the central region would maintain its efficacity for a much longer period of time. The center would not become smooth or lose its surface qualities, and we would not risk producing incorrect refiguring because of the weakening of its central portion and an annoying predominance of its edges.

.

Thus armed with two or three polishing laps of different sizes that are well-matched to the average curvature of the mirror, nothing will prevent us from beginning to refigure. Of the three examination procedures previously described, two of them will suffice to direct our work, the first and the last: namely, the microscopic examination of the image, and the direct viewing of the surface by means of rays that pass by a knife-edge mask. To determine which of these two procedures to use, we should recognize that the light source is the same for both, and that to pass from one to the other, we simply trade the microscope for the knife-edge mask.

.

With a preliminary test near the center of curvature, we explore the surface, and depending on the size of the local refiguring action indicated, we determine the size of the polishing lap which we should use. Then we place the mirror on its wooden basin carpeted by a piece of woolen cloth, and we begin to work.

.

In general, any glass surface that has remained for a time in contact with the air rebels at first against the action of the polishing lap, if one does not take care to clean it in such a way as to give it a state of perfect homogeneity. We dust it with powdered chalk, sprinkle a bit of water on that, and with a ball of cotton we create a paste all over the surface of the mirror. We let this dry, Then we take a new, loose, cotton puff, which we lightly pass over the surface. The dried white paste, which does not adhere well to the glass, comes loose, escapes over the edges, and allows the glass to reappear covered with a transparent veil. We continue to rub the glass lightly with a series of new cotton balls, and we see the veil slowly dissipate, and the surface of the glass ends up appearing pure and clean.

.

Even with a surface prepared in this manner, the polishing lap will still slide around at first and will only start “biting” after having passed a few times over the same sections. The points where it begins to work are distributed irregularly, here and there; there are regions where the rouge sticks and where one beings to feel the adhesion which reveals work in progress. These regions slowly enlarge, but until they have all merged into one another, the action of the polisher lacks uniformity, and there is a danger of altering the surface if one uses rouge, which has a lot of abrasive power. It is better to begin by using diatomaceous earth, which is easily spread on the paper, attacks the glass more slowly, and seems to have all the qualities desired for beginning to refigure.

.

When the lap is working equally well on all parts of the mirror, when it adheres equally well all over, one can replace the diatomaceous earth with English rouge, and then the work begins in earnest. This is the time to use the optical tests to find the figure of the solid of revolution that is, so to speak, superimposed on the mirror, and to plan on altering the figure by deciding which movements to give to the lap which, when repeated a large number of times and while rotating about the center, will be able to wear away the excess parts of the mirror. That motion, whatever it may be, once decided upon and adopted, should be executed without any change for about ten to 15 minutes, after which the mirror should be tested once again.

.

Doubtless it can happen that one has judged poorly and the movement employed gave a result other than expected. Even so, the test will provide some useful information; whereas, if one had varied the strokes several times between two mirror tests, the observed test results would not allow us to form any firm conclusions.

.

In any case, when the laps are well prepared, when they touch at their centers and not at their edges, when the paper does not form a skin and preserves its velvety finish, and the polishing powders do not migrate, there is no fear that the test result will display a marked disagreement with the strokes one has performed. The lap, if moved in procession on all the diameters, will assuredly produce a deepening of the central region. But if it is directed along a series of equal chords, one cannot avoid forming an annular furrow that will be further from the center the shorter the chords become. The width of the zone being worked will vary with the extent of the part that is rubbing and with the excess of curvature of the lap over that of the mirror. Polishing strokes that are directed on all chords will thus be enough to attack all the points on the surface; but in order that these lines may cross, one can also perform ellipses that are either elongated or widened. It is important to remember to check the status of the polishing lap. Also, the worker must walk all around the polishing station in a regular manner and check frequently the effect produced by each type of figuring stroke.

.

In this manner one will first of all produce a spherical figure, that is to say to obtain in the area of the center of curvature a well-defined image of the point of light, and produce a simultaneous extinction of the pencil of rays by cutting into that image with the knife-edge mask.

.

This first result, once accomplished, demonstrates the effectiveness of local refiguring and prepares the way for the work which must follow, the object of which is to arrive at a paraboloid of revolution by passing through the intervening ellipsoids. The point source of light, which was placed at the center of curvature, is brought closer to the mirror; the focus moves in the other direction; and the optical test, which just recently displayed a perfect surface, now reveals in this new position a beginning of spherical aberration. The image is surrounded by a slight nebulosity, which disappears once one forces it to come to a focus on the side towards the mirror, and which becomes more pronounced when one does the opposite: this is the sign of a positive aberration. The knife-edge mask which advances to cut off the image conveys to the surface the appearance noted earlier (figure 13). One thinks that one sees a central hill separated from the edge by an annular depression; but when one changes the distance back and forth between the knife-edge and the mirror, one finds in the stereoscopic appearance of this surface some variations that cause the bottom of the circular depression ring to approach, more or less, the center of the mirror.

.

A rational interpretation of this phenomenon leads one to recognize that there is an infinite number of ways to refigure a mirror so as to eliminate aberration. Thus, between the ellipsoid that is tangent to the center (figure 15) and the ellipsoid tangent to the edge of the spherical surface (figure 17) there is an infinity of ellipsoids which have a surface of contact with the actual surface (figure 16); their diameters can take on any value smaller than the diameter of the mirror.

A rational interpretation of this phenomenon leads one to recognize that there is an infinite number of ways to refigure a mirror so as to eliminate aberration. Thus, between the ellipsoid that is tangent to the center (figure 15) and the ellipsoid tangent to the edge of the spherical surface (figure 17) there is an infinity of ellipsoids which have a surface of contact with the actual surface (figure 16); their diameters can take on any value smaller than the diameter of the mirror.

.

Among those surfaces, towards which one should we strive? That depends on the dimensions of the mirror. When its diameter is not greater than 25 or 30 centimeters, it is best to use the strokes that are easiest to perform, namely those which leave the edge zone alone and work primarily on the central portion of the mirror. But when the mirror becomes larger, it is better to be guided by other considerations, and to search for the refiguring methods that will lead one to remove the smallest possible amount of glass. One therefore divides the refiguring between the edge and the center, and does nothing to the zone that corresponds to the circle of contact, as one can see in figure 16. In any case, one ends up by effecting an apparent leveling of the surface and at the same time destroying the aberration which surrounded the image of our point source of light.

.

This result being verified, we repeat the same operation for a more advanced position of the conjugate foci; the mirror changes by taking on a more and more pronounced ellipsoidal form. Passing this way from station to station, the two foci proceed in opposite directions, and they show, in increasing the distance between them, that the ellipsoid is undergoing a corresponding elongation.

.

Finally, the image of the point, which had been advanced farther and farther and is still free of aberration, finds itself at the very end of the experimental line laid out earlier. At this point, with a final refiguring, we need to push it all the way to infinity while still being fully corrected. The longer the experimental line, the less this last step will appear to be hazardous. Nonetheless, we need to stay within practical limits. We have assumed that in our operation, the distance between the two farthest workstations is at most equal to five times the focal length of the mirror. Let us preserve this assumption, and let us show that our final refiguring operation can still be subjected to a rigorous exam.

.

When the image of the point of light has reached the end of the line, the point source itself is still at a certain distance from the principal focus of the mirror, and since the latter point is half way to the center of curvature, its position can be determined. Let us call F the principal focal point, and F’ the present position of our point source of light. We will call F” one of its previous positions, with the condition that F’F” will be equal to FF’. By virtue of the previously explained principles on the progress of positive and negative aberrations, it so happens that if we bring the point source to F’, the appearances will appear as if the mirror had become parabolic, and that the point source had remained at F.

.

Let us examine now the relief of the figure that appears now, and then, while bringing the light source towards F’, let us try to reproduce this relief by modifying the surface with a final refiguring session. In this way, we can make the image pass to infinity without any aberration, and we can impart to the mirror a figure that is very near to a paraboloid of revolution. But even if it is impracticable to go and observe the image at infinity whence we have pushed it, nothing could be easier than to verify the result we have obtained by switching the object and its image. To do this, simply take as a target an outside object, located at as large a distance as one desires, and observe it with the mirror mounted in a Newtonian telescope. The image must then show itself to be free of aberration, and to show diffraction lines around the object. If this object is a point of light, or if it takes on the appearance of a square grid, then the three testing procedures described earlier become applicable at the prime focal point. If any perceptible defects remain that escaped our last refiguring session, there is still time to do another one and to make the defect disappear.

.

To sum up, the method we have just described consists of subjecting our surfaces to optical tests, and then modifying them via hand refiguring sessions until they appear to have no more defects. The nature of the situation has permitted us to initiate, on the one hand, various testing methods, and on the other, various methods of working the surface of the glass. These two procedures allow us to arrive precisely at the result we were attempting to obtain. But if the testing procedures are not sensitive enough, or if our refiguring methods were less delicate, then this method would have failed. However, our experiments have been quite successful.

.

Let us also suggest that our methods might not be applicable to metallic mirrors, for it has not been shown that the crystalline alloys which make up those mirrors up until now are capable of bearing an indefinite series of refiguring operations as do glass mirrors with polishing laps.

.

But even though we have failed in trying to extend to metal mirrors the benefits of local refiguring, this is not a great loss, because even if it were successful, the benefit would only be temporary. The advantage would be compromised from the moment that the metal polish was altered under the chemical influence of the air. By comparison, once a curvature is made in glass, one can consider it to be permanent. The alterations and tarnishing that will occur with time only affect the layer of silver metal that is deposited on the mirror afterwards by an operation that can be renewed indefinitely.

To perform this experiment, we create a point source of light to be used as the origin of the rays to be emitted. We glue a short-focal-length plano-convex lens onto one of the two identical faces of a small, totally-reflecting right angle prism (Plate 1, figure 1). A lamp flame is placed 20 to 30 cm away from the axis of the experiment, and its horizontal rays illuminate this lens, which is perpendicular to those rays of light. The converging rays of light are completely reflected by the hypotenuse surface of the prism. These rays then form, outside of the prism, an image of the flame on a small opaque screen. This screen is pierced by a pinhole, which we can consider to be a point. This screen is placed near the center of curvature of the mirror and is so oriented as to fully illuminate the mirror. A microscope is used to examine the conjugate focus.

To perform this experiment, we create a point source of light to be used as the origin of the rays to be emitted. We glue a short-focal-length plano-convex lens onto one of the two identical faces of a small, totally-reflecting right angle prism (Plate 1, figure 1). A lamp flame is placed 20 to 30 cm away from the axis of the experiment, and its horizontal rays illuminate this lens, which is perpendicular to those rays of light. The converging rays of light are completely reflected by the hypotenuse surface of the prism. These rays then form, outside of the prism, an image of the flame on a small opaque screen. This screen is pierced by a pinhole, which we can consider to be a point. This screen is placed near the center of curvature of the mirror and is so oriented as to fully illuminate the mirror. A microscope is used to examine the conjugate focus.

After the presentation of the first 20 cm

After the presentation of the first 20 cm