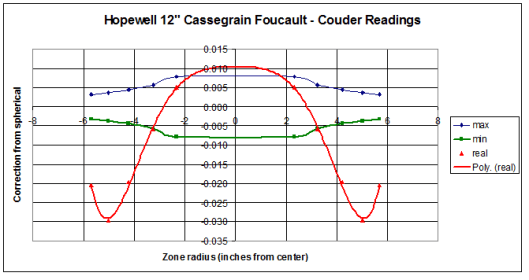

Tags

algebra 2, algebra two, beauty, benoit mandelbrot, complex numbers, education, imaginary numbers, julia set, mandelbrot set, Math, strange, weird

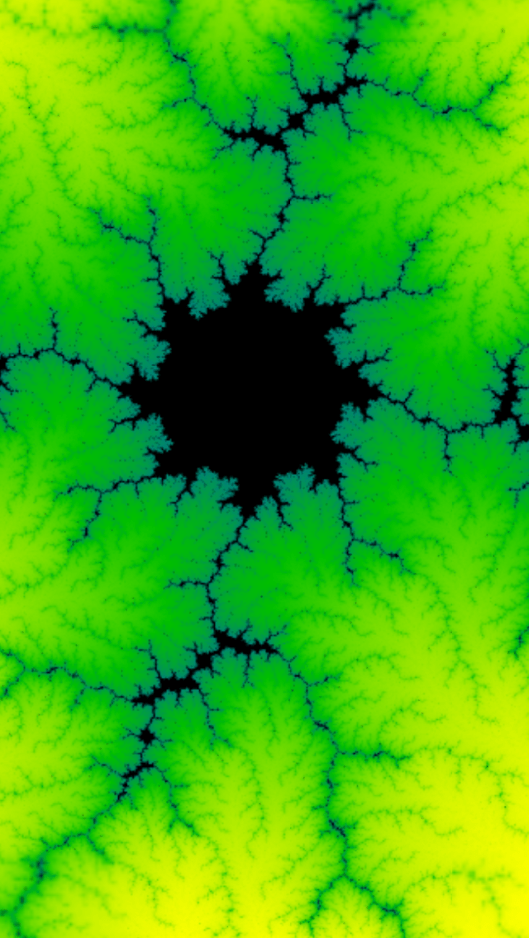

When I taught math, I tried to get students to see both the usefulness and beauty of whatever topic we were discussing. The most beautiful mathematical objects I know of are the Mandelbrot and Julia sets, which in my opinion should be brought up whenever one is studying imaginary and complex numbers.

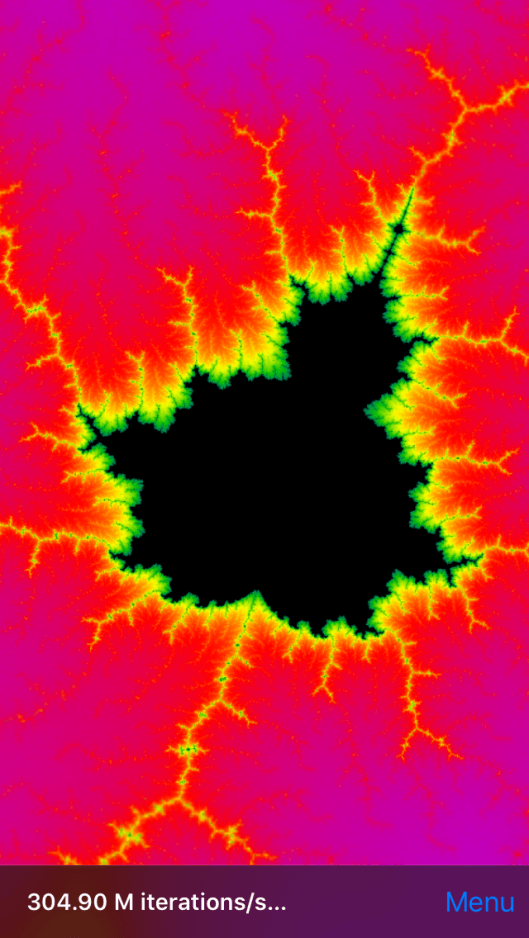

To illustrate what I mean, here are some blown up pieces of the Mandelbrot set. Below, I’ll explain the very simple algebra that goes into making it.

I made these images using an app called FastFractal on my iPhone. The math goes like this:

Normally, you can’t take the square root of a negative number. But let’s pretend that you can, and that the square root of negative one is the imaginary number i. So the square root of -16 is 4i. Furthermore, we can invent complex numbers that have a real part like 2, or 3.1416, or -25/17, or anything else, and an imaginary part like 3i or -0.25i. So 2-3i is a complex number.

Ok so far?

We can add, subtract, multiply and divide real, imaginary and complex numbers if we want, just remembering that we need to add and subtract like terms, so 4+3i cannot be simplified to 7i; it’s already as simple as it gets. Remember that i multiplied by i gives you negative one!

Interesting fact: if you multiply a complex number (say, 4+3i) by its conjugate (namely 4-3i) you get a strictly REAL answer: 25! (Try it, using FOIL if you need to, and remember that i*i=-1!)

Furthermore, let us now pretend that we can place complex numbers on something that looks just like the familiar x-y coordinate plane, only now the x-axis becomes the real axis and the y-axis becomes the imaginary axis. So our complex number 4+3i is located where the Cartesian point (4, 3) would be.

Ok — but what’s the connection to those pretty pictures?

It’s coming, I promise!

Here’s the connection: take any point on the complex plane, in other words, any complex number you wish. Call it z. Then:

(1) Square it.

(2) Add the original complex number z to that result.

(3) See how far the result is from the origin.

(4) Repeat steps 1 – 3 a whole lot of times, always adding the original z.

One of two things will happen:

(A) your result stays close to the origin, OR

(B) it will go far, far away from the origin.

If it stays close to the origin, color the original point black.

If it gets far away, pick some other color.

Then repeat steps 1-4 for the point “right next” to your original complex point z. (Obviously, the phrase “right next to” depends on the scale you are using for your graph, but you probably want fine coverage.)

When you are done, print your picture!

If we start with 4+3i, after one round I get 11+27i. After two rounds I get -604 + 597i, which is very far from the origin, so I’m going to stop here and color it blue. I’ll also decide that every time a result gets into the hundreds after merely two rounds, that point will also be blue.

Now let’s try a complex point much closer to the origin: how about 0.2+0.4i? I tried that a bunch of times and the result seems to converge on about 0.024+0.420i — so I’ll color that point black.

This whole process would of course be very, very tedious to do by hand, but it’s pretty easy to program a graphing calculator to do this for you.

When Benoit Mandelbrot and others first did this set of computations in 1978-1980, and printed the results, they were amazed at its complexity and strange beauty: the border between the points we color black and those we color otherwise is unbelievably complicated, even when you zoom in really, really close. Who woulda thunk that a simple operation with complex numbers, that any high school student in Algebra 2 can do and perform, could produce something so beautiful and weird?

So, why not take a little time in Algebra 2 and have students explore the Mandelbrot set and it’s sister the Julia set? They might just get the idea that math is beautiful!!!