How to make a spectroscope – cheap!

04 Friday Jul 2025

Posted in astronomy, astrophysics, education, Optics, Telescope Making

04 Friday Jul 2025

Posted in astronomy, astrophysics, education, Optics, Telescope Making

24 Friday Jan 2025

Posted in astronomy, education, Optics, Telescope Making

Tags

astronomy, Astrophotography, ATM, celestron, dobsonian, Optics, science, space, StarSense, Telescope, testing

Astronomy is moving so fast, it’s amazing.

We only truly discovered the nature of galaxies, of nuclear fusion, and of the scale of the universe a mere century ago.

Dark matter was discovered by Vera Rubin just over 40 years ago and dark energy a few years later, just before the time that both professional and amateur astronomers began switching over to CCD and later CMOS sensors instead of film

The first exoplanet was discovered only 30 years ago, and the count is now up to almost six thousand of them (as of 1/21/2024).

While multi-billion dollar space telescopes and giant observatories at places like Mauna Kea and the Atacama produce the big discoveries, amateur astronomers with a not-outrageous budget can now afford to purchase relatively small rigs armed with excellent optics and complete computer control, and lots of patience and hard work, can and so produce amazing images like the ones here https://www.novac.com/wp/observing/member-images/ or this one https://www.instagram.com/gaelsastroportrait?igsh=cjMzYWlqYjNzaDlw, by one of the interns on this project. Gael’s patience, cleverness, dedication and follow-through are all praiseworthy.

However, it is getting harder and harder every year for people to see anything other than the brightest planets, because of ever-increasing light pollution; the vast majority of the people in any of the major population centers on any continent have no hope of seeing the Milky Way from their homes unless there is a wide-spread power outage. Here in the US, such power outages are rare, which means that if you want to go out and find a Messier object, you pretty much cannot star-hop, because you can only see four to ten stars in the entire sky!

One choice is to buy a completely computer-controlled SCT like the ones sold by Celestron. They aren’t cheap, but they will find objects for you.

But what if you don’t want another telescope, but instead want to give nice big Dobsonian telescope the ability to find things easily, using the capabilities inside one’s cell phone?

Some very smart folks have been working on this, and have come up with some interesting solutions. When they work, they are wonderful, but they sometimes fail for reasons not fully understood. I guess it has something to do with the settings in the cell phone being used.

The rest of this will be on one such solution, a commercial one called StarSense from Celestron that holds your phone in a fixed position above a little mirror, and you aim the telescope and your cell phone’s camera at something like the top of a tower far away. Then it uses both the interior sensors on your cell phone and images of the sky to figure out where in the sky your scope is pointing, and tells you which way to push it to get to your desired target.

When it works, it’s great. But it sometimes fails.

You have to buy an entire set from Celestron – one of their telescopes (which has the gizmo built in) along with the license code to unlock the software.

You supply the cell phone.

The entire setup ranges in price from about $200 to about $2,000. You cannot just buy the holder and the code from them; you must buy a telescope too. I already had decent telescopes, which I had made, so I bought the lowest-priced one. I then unscrewed the plastic gizmo, and carved and machined connection to a male dovetail slide for it. I also fastened a corresponding female dovetail to each of my scopes. The idea was to then slip this device off or onto whichever one of my telescopes is going to get used that night, as long as I that has a vixen dovetail saddle, and put inexpensive saddles on several scopes I have access to.

Here are some photos of the gizmo:

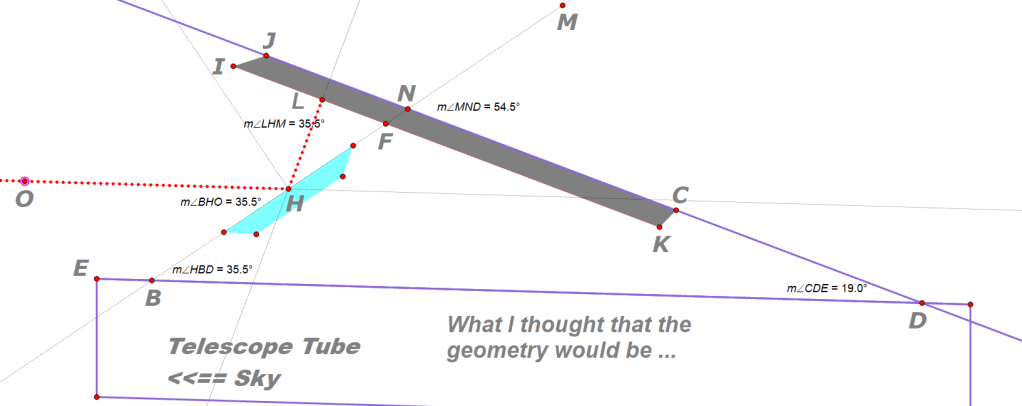

NCA’s current interns (Nabek Ababiya and Gael Gomez) and I were wondering about the geometry of the angles at which StarSense would aim at the sky in front of the scope. My guess had been that Celestron’s engineers would make the angles of their device so that the center of the optical pencil hitting the lens dead-on at 90 degrees, and hence coning to a focus at the central pixel of the CMOS sensor, would be parallel to the axis of the telescope tube.

We didn’t want to touch the mirror, because it’s quite delicate. But as a former geometry teacher, I couldn’t leave this one alone, so along with Gael and Nabek I made some diagrams and figured out what the angles had to be if the axis of the StarSense app’s image were designed to be precisely parallel to the axis of the telescope.

In my diagram below, L is the location of the Lens, and IJCK is the cell phone lying snug in its holder. The user can slide the cell phone left and right along that line JD as we see it here, or into out of the plane of the page, but it is not possible to change angle D aka <CDE – it’s fixed by the factory molds to be some fixed angle that we measured with various devices to be 19.0 degrees.

Here is a version of the diagrams we made that showed what we predicted all the angles would be so that optical axis OH will be parallel to the tube axis EBD, and that lens angle ILH is a right angle. We predicted that the mirror’s axis would need to be tilted upwards by an angle of 35.5 degrees (anle HBD).

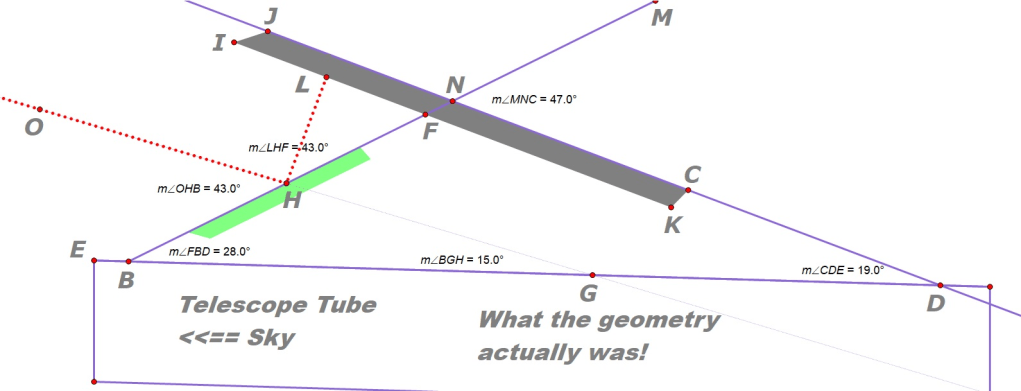

To our surprise, our guesses and calculations were all wrong!

After careful measurements we found that Celestron’s engineers apparently decided that the optical axis of the SS gizmo should instead aim the cell phone’s camera up by 15.0 degrees (angle BGH below). The only parallel lines are the sides of the telescope tube!

We used a variety of devices to measure angle FBD and MNC to an accuracy of about half a degree; all angles turned out to be whole numbers.

Be that as it may, sometimes it works well and sometimes it does not.

Zach Gleiberman and I tested it on an open field in Rock Creek Park here in DC back in the fall of 2024, using the Hechinger-blue 8 inch dob I made 30 years ago and still use. We found that SS worked quite well, pointing us quite accurately to all sorts of targets using my iPhone SE. The sky was about as good as it gets inside the Beltway, and the device worked flawlessly.

Not too long afterwards, I decided to try out an Android-style phone (a REVVL 6 Pro) so that I wouldn’t have to give up my cell phone for the entire evening at Hopewell Observatory. I was unpleasantly surprised to find that it didn’t work well at all: the directions were very far off. I thought it might be because the scope in question had a rather wide plywood ring around the front of its very long tube, and that perhaps too much of the field of view was being cut off?

Why it fails was not originally clear. I thought nearly every modern phone would work, since for Androids, it just needs to be later than 2016 and have a camera, an accelerometer, and gyros, which is a pretty low bar these days. However, my REVVL 6 Pro from T-Mobile is not on the list of phones that have been tested to work!

Part of my assumption that the axis of the SS gizmo would be parallel to the axis of the scope was an explanation that StarSense on had such a large obstruction in front of the SS holder, in the form of a wide wooden disk reinforcing the front of a 10″ f/9 Newtonian, that the SS was missing part of the sky. We now know that’s not correct. It’s an interface problem (ie software) problem.

We think.

02 Saturday Nov 2024

Posted in astronomy, astrophysics, Math, Optics, science, Telescope Making

Tags

astronomy, ATM, data, FigureXP, foucault, measurement, millies-lacroix, paraboloid, Telescope

Alan Tarica, Pratik Tambe, Tom Crone and I have been pulling our hair out for a couple of years, trying to use cameras and software to measure the ‘figure’ of the telescope mirrors that we and others produce in our telescope-making class.

There has been progress, and there has been frustration.

I think we finally succeeded!

Some of the difficulties have been described in previous posts. In brief, we want our mirrors to be really, really close to a perfect paraboloid. There are many ways of doing those measurements and seeing whether one is close enough, but none of those methods are easy!

(By the way, one needs the entire mirror to be within one-tenth of a wave-length of green light of that ideal paraboloid! That’s extremely tiny, and equivalent to the thickness of a pencil over a ten-mile diameter!)

I think I can finally report a victory. My evidence is this graph that I made just now, using data that Alan and I gathered last night with our setup, which consists of a surveillance camera coupled to an old 35mm SLR film camera lens, which is mounted on a linear actuator screw connected to a stepper motor controlled by an Arduino and a Python app developed by Pratik.

Something seemed to be always a bit — or a lot — ‘off’.

Until today, when I converted everything to millimeters and used the criterion set out by Adrien Millies-Lacroix in an article he wrote in Sky & Telescope back in 1976.

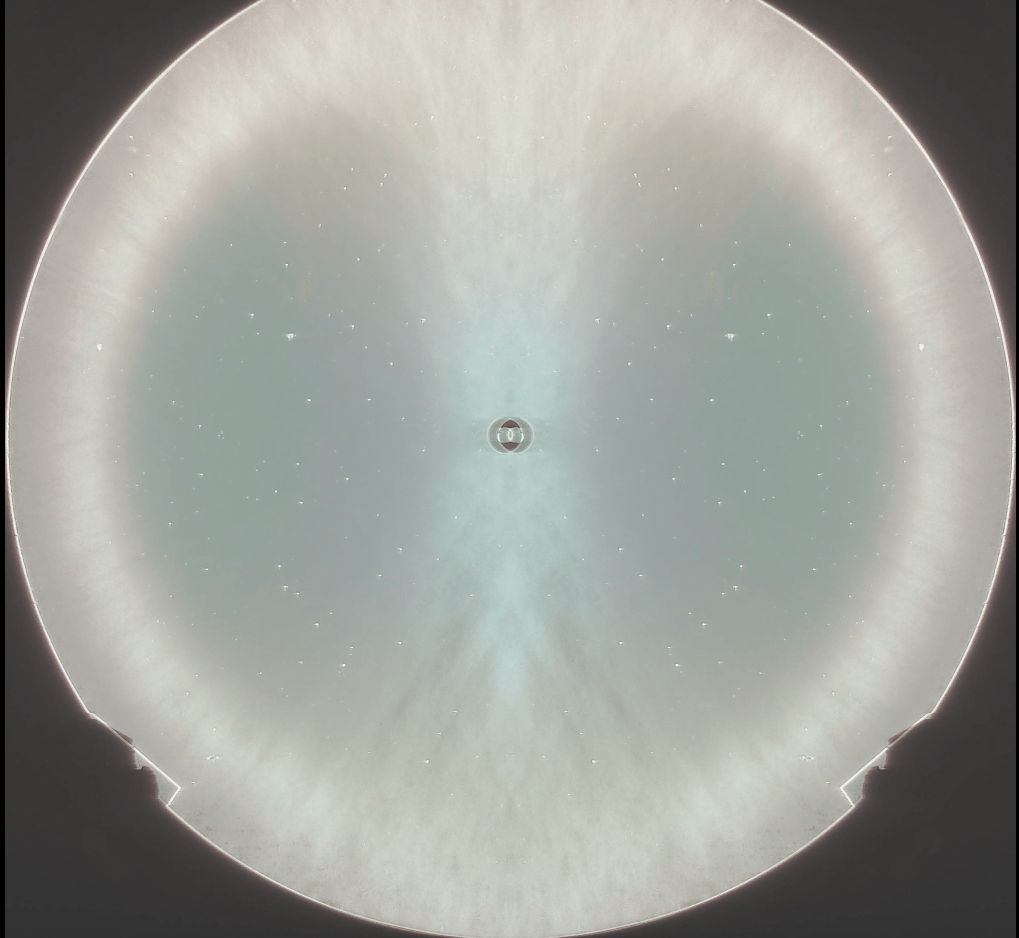

The blue dots just above the x-axis are the measurements for this one particular mirror with a diameter of 8″ and a radius of curvature of 77 inches.

The dotted blue curve in the middle of the image is the best-fit parabola for those dots. Notice that the R-squared value (variance) for that curve is not great: 0.3599.

But that variance isn’t important. What is important is the green and orange blobs and curves above and below the blue ones.

The green and orange curves are the upper and lower allowable limits for the measurements of this particular mirror, using the

Clearly, the blue dots are all well within the green and orange curves.

Which means that this mirror is sufficiently parabolized.

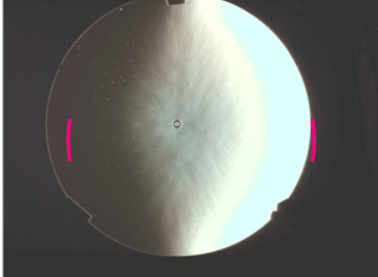

The fact that the blue dots don’t fit the dotted line perfectly, and behave pretty oddly at positive or negative 80 millimeters, both agree with the fact that we can see on the photos that the surface of this mirror is rather rough, as you can see in the images below. Note also that the image labeled ‘Step 6’ found not one, but two null zones on the right, indicated by two vertical blue lines.

So, finally, we have an algorithm that gives good measurements! What I still want to do is to automate all the spreadsheet calculations that I just did today. Perhaps we can upload them to something like FigureXP by Dave Rowe and James Lerch.

Thanks very much to all those who have helped, whom I should look up and name here.

Caveat: This method can give really ridiculous measurements close to the center and close to the edge.

PS: if anybody wants the raw data, just email me at gfbrandenburg at gmail dot com.

16 Wednesday Oct 2024

Posted in astronomy, Hopewell Observatorry, Optics, Safety, science, Telescope Making

Come to Bull Run Mountain for a free night under the stars looking at a variety of targets using the telescopes at the Hopewell Observatory on Saturday, October 26, 2024. If it’s cloudy, we will try again on the next evening, Sunday the 27th.

You are invited, but will need to RSVP and, in this litigious age, must agree to a waiver of liability for anything that might happen up there, like tripping over rocks and trees. The waiver also includes detailed driving directions.

Click here for the RSVP form:

But if you take the risk you can view, for free, Venus, Saturn and its rings, Jupiter and its moons, Uranus, Neptune, the current comet Atlas, the Milky Way, and a whole bunch of nebulae, galaxies, Messier objects, and beautiful double stars.

We suggest arriving near sundown, which will happen near 6:15 PM. It will get truly dark about an hour later. You can stay until midnight, if you like.

There are no street lights near our observatory, other than some dimly illuminated temporary signs we put along the path, so you will probably want to bring a flashlight of some sort. In the operations cabin we have a supply of red translucent plastic film and tape and rubber bands so that you can filter out everything but red wavelengths on your flashlight. This will help preserve everybody’s night vision.

Hopewell is located on the first ridge of the Appalachian mountain chain that you see as you drive west from the DC beltway, near Haymarket. Our elevation is about 1100 feet, and we have much less of a problem with dew than other observing spots in northern Virginia. The last two miles of road are dirt and gravel, and you will need to walk about 200 meters/yards from where you park. Some parts of the road are pretty rough, so don’t drive anything with low clearance underneath. Our parking spaces are pretty limited, so consider car-pooling if possible. Handicapped persons or telescopes can be dropped off at the observatory.

We do have electricity, and a heated cabin, but since we have no running water, we use bottled water, hand sanitizer, and a pretty nice outhouse. We will have the makings for tea, coffee, and hot cocoa in that cabin.

If you like, you can bring a picnic dinner and a blanket or folding chairs, and/or your own telescope or binoculars, if you own one and feel like bringing them. We have outside 120VAC power, if you need it for your telescope drive.

At this time of year, the bothersome insects have mostly gone dormant, but feel free to use your favorite bug repellent, (we have some). Remember to check yourself for ticks after you get home.

We have a variety of permanently-mounted and portable telescopes of different designs, some commercial and some made by us. Two of our telescope mounts are permanently installed in the observatory under a roll-off roof. One of the mounts is a high-end Astro-Physics mount with a 14” Schmidt-Cassegrain and a 5” triplet refractor. The other mount was manufactured about 50 years ago by a firm called Ealing, but the motors and guidance system were recently completely re-done by us with modern electronics using a system called OnStep. We didn’t spend much cash on it, but it took us almost a year to solve a bunch of mysteries of involving integrated circuits, soldering, torque, gearing, currents, voltages, resistors, transistors, stepper drivers, and much else. We could not have completed this build without a lot of help from Arlen Raasch, Prasad Agrahar, Ken Hunter, and the online “OnStep” community.

We also have two home-made Dobsonian telescopes (10″ and 14″ apertures) that we roll out onto our lawn, and have been lent a pair of big binoculars on a parallelogram mount.

The location of the observatory is approximately latitude 38°52’12″N, longitude 77°41’54″W.

Click here for the RSVP form to get detailed directions. You must sign the waiver to visit. If we cancel on Saturday the 26th because of bad weather, we will notify you by email and will try again on Sunday the 27th.

06 Tuesday Aug 2024

Posted in astronomy, astrophysics, Optics, science

Tags

alt-az, astronomy, electronics, focus, Hopewell Observatory, light pollution, optical tube assembly, Optics, refractor, solar system, Telescope, Washington

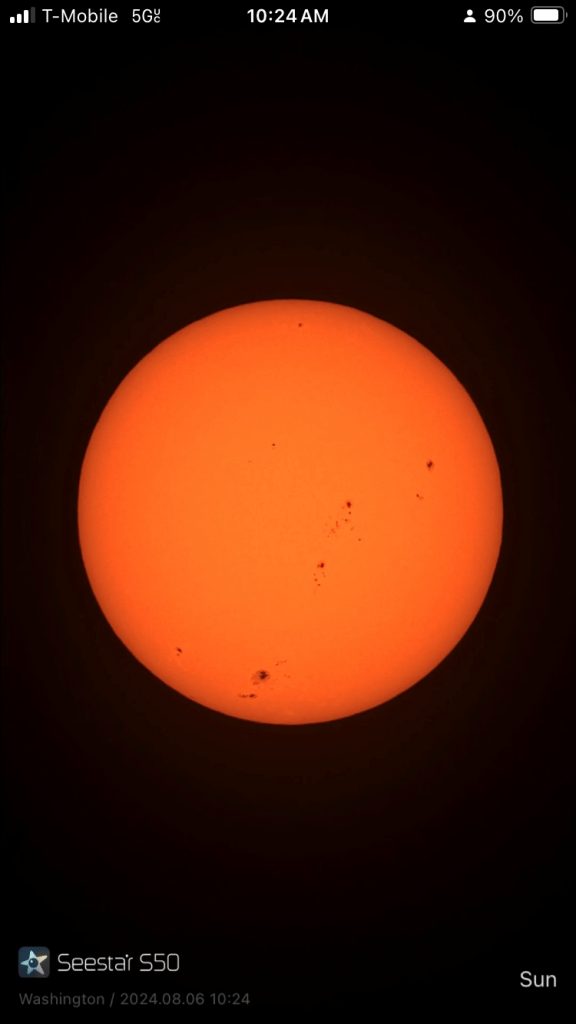

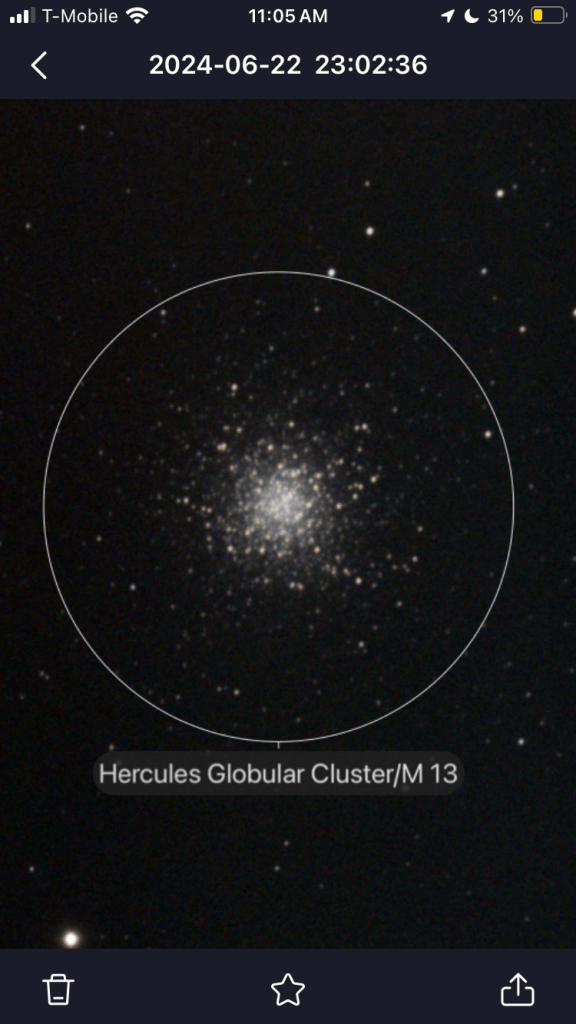

Look what this little thing can do that I’ve always failed at myself, even with an entire observatory at my disposal: take decent astrophotos.

Here it is on a home made tripod, taking photos of the sun. Notice the reflective solar filter. Here are two images:

The device woke up, and after less than a minute of self’s-calibration, it pointed very accurately at the sun and focused itself perfectly. It produces a continuous feed; I even did 100 frames of a time-lapse. It’s all stored on my cell phone but I can share the photos or even live views with folks nearby.

And from night time spots here in DC and NOVA:

This can take tolerable astrophotos even when surrounded by streetlights!

.

04 Thursday Jul 2024

Posted in astronomy, Hopewell Observatorry

Tags

astronomy, ealing, Ealing mount, Hopewell, Hopewell Observatory, Moon, planet, solar system, Telescope

These were made by Gael Gomez, a recent HS grad who visited on Monday, July 1.

08 Friday Dec 2023

Posted in astronomy, astrophysics, History, nature, Safety, science, Uncategorized

Tags

air, earth, exoplanets, extinction, fossil fuels, galaxies, heaven, hell, life, light years, Moon, planets, space, space travel, stars

When I show people things in the sky with a telescope, I want to help them to realize how lucky we are to live on a nice, warm, wet little planet in a relatively safe part of a medium-large galaxy.

I also want them to realize that if we aren’t careful, we could turn this planet into one of those many varieties of deadly hell that they are viewing in the eyepiece.

We should be very thankful that this planet got formed in a solar system that had sufficient oxygen, silicon, iron, nitrogen, and carbon for life as we know it. We are fortunate that all of those ‘metals’ I just listed (as astronomers call them) got cooked up in cycle after cycle of stars that went boom or whooshed their outer layers into the Milky Way. We are lucky to be alive at the far multicellular side of the timeline of life on Earth*, and that no star has gone supernova in our neighborhood recently or aimed a gamma-ray burst directly at us.

We are exceedingly lucky that a meteorite wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years and allowed our ancestors, the mammals, to take over. We can rejoice that most of us in the USA can have our physical needs (food, shelter, clean water, clean air, and communication) taken care of by just turning a knob or a key, or pushing a button, instead of hauling the water or firewood on our backs. (There are, obviously, many folks here and abroad who live in tents and who have essentially none of those nice things. We could do something about that, as a society, if we really wanted to.)

I am often asked whether there is life elsewhere. My answer is that I am almost positive that there are lots of planets with some form of life in every single galaxy visible in an amateur telescope. But there is no possible way for us humans to ever visit such a planet. Nor can aliens from any exoplanet ever visit us, whether they be single-celled organisms or something you would see in a Sci-Fi movie.

Yes, it is possible to send a handful of people to Mars, if we are willing to spend enormous sums of money doing so, and if the voyagers are willing to face loss of bone and muscle mass, and the dangers of lethal radiation, meteorites, accidental explosions, and freezing to death. If they do survive the voyage, then by all means, let them pick up some rocks and bring them back for analysis before they die.

But wait: we already have robots that can do that! Plus, robots won’t leave nearly as many germs behind as would a group of human beings. And we already know a lot about how Mars looks, because of all the great photos sent back by ESA, JAXA, NASA and others for some decades now. You can see photos taken by NASA at JMARS, which I highly recommend. (https://jmars.asu.edu/ )

While one can justify sending a few brave folks to Mars for a little while, it is completely insane to think that we can avoid our terrestrial problems by sending large populations there. Mars is often colder than Antarctica, is close to waterless, has poisonous perchlorates in its soil, no vegetation whatsoever, and no atmosphere to speak of. How would millions or billions of exiles from Earth possibly live there? Do you seriously think they can gather enough solar energy to find and melt sufficient water to drink and cook and bathe and grow plants and livestock in the huge, pressurized, aluminum cans they would need to live in? No way.

I wish there was some way to get around the laws of physics, and that we could actually visit other exoplanets. But there isn’t, and we can’t. I’ve seen estimates that accelerating a medium-sized spaceship to a mere 1% of the speed of light would require the entire energy budget of the entire human population of the planet for quite some time. (For example, see https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/447246/energy-requirements-for-relativistic-acceleration )

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that you could actually generate enough energy to accelerate that spaceship with nuclear fusion or something else that doesn’t violate the laws of physics as far as we know.

The next problem is the distance. It’s a bit over 4 light years to the nearest known exoplanet in a straight line, (compared with under 2 light-seconds for the Moon or about 35 light minutes for Jupiter). The table below gives the number of planets lying each extra solar system that are thought to be terrestrial (as opposed to gas giants) and to be within their stars’ habitable zones. Nobody knows if there is any life on any of those planets right not, but it is possible that astronomers may one day figure out a very effective way to test for extra-solar life. Let us suppose that a few of the ones in this list do have breathable atmospheres and are neither too cold nor too hot, have a fair amount of liquid water, and are protected from nasty radiation by magnetic fields and belts.

Unfortunately, a one-way trip to Proxima or Alpha Centauri for any possible spaceship, at one percent of the speed of light, (3,000 km per second), in a straight line, and pretending that you don’t need years and years to both accelerate and decelerate, would take over four centuries. And that’s for the very closest one! All the other planetary systems are many multiples of that distance! See this or this table:

Our fastest spacecraft so far, the Parker Solar Probe, reaches the insanely fast speed of 190 km/sec, but that’s still fifteen times slower than my hypothetical 1% of c. At the speed of Parker, it would take around six thousand years to reach the Proxima Cen planetary system! If all goes well!

Do you seriously think that a score or so generations of humans would all agree, century after century, that they, and their descendants — born and raised in a big metal box rushing through space — for the entire 400 years, would consent to live in a large metal box with no gravity to speak of, subject to who knows how many blasts of gamma rays, x-rays, and super-high-energy cosmic particles? What are the chances that each single generation would agree to stay the course and that not a single meteorite going the other direction, over a course of four centuries, would happen to smash into the space ship and instantly disable all the life support systems and kill all the passengers, quickly or slowly?

And how do you keep alive all the animals we would need to feed us upon arrival? I guess you compost all the poop from all the cattle, chickens, and so on. But do you also bring zillions of insects and tons of plant seeds as well, knowing full well that if you do so, then you lose the vast majority of the information you could have learned about an actual, functioning, extra-solar ecosystem like nothing we can possibly imagine.

The argument is made that perhaps the travelers would be put into suspended life. If that were possible, and nothing went wrong, upon arrival, they could take a triumphant group selfie and put it into a radio message back to Earth saying, “Hi, we made it, wish you were here…” That reply will of course take four years to reach Earth. Would people back on Earth still remember the handful of people who began the trip out, made over four centuries earlier? What will the humans back on earth remember about the absolutely prodigious effort expense that their ancestors had made to build and power that rocket, 20 generations or so earlier?

Let us suppose they have the tremendous luck to find, after 4 to 10 centuries of travel, a nice warm exoplanet with water, oxygen-producing life, and air that we can breathe.

Unfortunately, there is an overwhelming chance that there would be no humanoids or any other Sci-Fi characters. The chances are that creatures that look like insects, crustaceans, fish and salamanders are the most highly-organized life forms – at best; after all, for most of the existence of life on earth, it was single-celled organisms! Our travelers would have to have to build an entire urban and agricultural infrastructure *from scratch*, with no help. They could only do that if the plants and animals they brought from Earth are able to flourish.

The return trip, if desired, would of course take another four or more centuries, if the handful of travelers can find a proper power source and if they can figure out how to create, completely from scratch, an entire agricultural and industrial instructure. They would have to figure out where the natural resources of that planet (wood? minerals? energy sources?) are located, and how they can make use of them, to build something like the incredibly precise absolutely enormous rocket-building industries we have here, on a hypothetical planet that has never even had any mammals living on it.

If these voyagers should run into any technical problem while doing trying to build a modern civilization from nothing, fat chance of getting a prompt reply from Earth, since the question would take years to reach its home base back here!

Yes, the very closest exoplanets are a mere 4 LY away, but the others are all much, much farther away, so one-way trips for ones within 10 parsecs, i.e., in our tiny corner of our galaxy, at one percent of the speed of light, would require a thousand to three thousand years to reach. Each way.

Forget it. Just send a radio message, and see if we get a reply. Oh, wait – we’ve been doing that for several decades so far. No reply so far.

Speaking of radio – it’s only 120 years since Marconi first sent a very crude radio message from a ship to a station on land, and now we routinely use enormous parts of the entire electromagnetic spectrum for all sorts of private and public purposes, including sending messages like this one. Astronomers are able to gather amazing amounts of information via the longest radio waves to the very shortest gamma rays and make all sorts of inferences about worlds we have never seen at optical wavelengths. In addition, we have begun detecting gravity waves from extremely distant and powerful events with devices whose accuracy is quite literally unbelievable.

There is no planet B. We must, absolutely must, take care of this one, lest we turn into one of those freezing or burning variations of hell that we see through our eyepieces. Think I’m being alarmist? We now know this nice little planet Earth is more fragile than we once believed. It has been discovered that life was almost completely wiped out on this planet several times. The Chixculub impact I mentioned earlier, the Permian extinction and Snowball Earth are just three such events.

More recently, folks thought it was impossible for people to cause the extinction or near-extinction of the unbelievably huge flocks and herds and schools that once roamed the earth: passenger pigeons, buffaloes, cod, salmon, redwoods, elms, chestnuts, elephants, rhinos, tropical birds, rainforests, and so on, but we did, and continue to do so. The quantities of insects measured at site after site around the world have plummeted by 30 to 70% and more, over just a few decades, and so have the numbers of migratory birds observed on radar feeds. Light pollution, the bane of us amateur and professional astronomers, seems to be partly responsible for both the insect and bird population declines. The rise in the levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperatures are very scary.

In addition, we are dumping incredible amounts of plastic into the oceans, and rising water temperatures are causing coral reefs around the world to bleach themselves and die, while melting glaciers are causing average sea levels rise and threaten more and more low-lying cities.

What’s more, only a very tiny fraction of our planet’s mass is even habitable by humans: the deepest mine only goes down a few miles, and people die of altitude sickness when they climb just a few miles above sea level. Most of the planet is covered by ocean, deserts, and ice cap. By volume, the livable part of this planet is infinitesimal, and the temperatures on it are rising at an alarming rate.

Will we be able to curb the burning and leaking of fossil fuels sufficiently so as to turn around the parts of global warming caused by increases in carbon dioxide and methane? I am not optimistic, given that the main emitters have kept essentially none of the promises that they have been making to those various international gatherings on climate, and graphs like this one, taken from: https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels

I have been wondering whether we may need to reduce temperatures more directly, by putting enough sulfur compounds into the stratosphere. We have excellent evidence that very violent volcanic eruptions have the power to lower global temperatures with the sulfates they put into the stratosphere. It would not be great for ground-based astronomy if such compounds were artificially lofted high into the atmosphere to lower global temperatures, and we won’t know for sure exactly which areas of the planet would benefit and which would be harmed, but at least it’s an experiment that can be stopped pretty easily, since the high-altitude sulfates would dissipate in a few years. High-altitude sulfur compounds do not seem to cause the obvious harm that SO2 does at the typical altitude of a terrestrial coal-burning power plant.

Adding iron to the oceans to increase the growth of phytoplankton, which then consumes CO2, dies, and settles to the bottom of the ocean, has been tried a number of times, but doesn’t seem to have a very large effect.

I agree that large-scale injection of sulfates into the stratosphere is scary. I also agree that there is a whole lot of unknown unknowns out there and inside of us, and we are being very short-sighted, as usual.

But — does anybody have better solutions?

Can we engineer our way out of the mess we are making on this planet – the only home that humans will ever have?

There is cause for optimism:

But let us not turn this planet – the only home we will ever know – into one of the barren, freezing or boiling versions of hell we see in the eyepieces of a telescope.

I have raised pigs, and I noticed that they never foul their own beds, if they are given any room to move around. Let’s be better than pigs and stop trying to extract riches in the short run while destroying the lovely planet we all love in the long run!

Heaven is not somewhere else.

It’s right here, if we can keep it that way and fix the damage we have done.

======================================================

* For five-sixths of the roughly 3.7-billion-year time line of life on earth, all living things were single-celled microbes (or microbes living together in colonies). We mammals have only been important for the last 1.7% of that time, (ie since the dinosaurs died out 66 million years ago), the first known writing system was invented a few millennia ago, and Marconi only sent the first ship-to-shore radio message 130 years ago, which is an infinitesimally small fraction of 3.7 billion. Home radios only became popular 100 years ago.

Assuming that planets and stars are created at random times in the history of the universe, and assuming that a certain amount of enrichment of the interstellar medium by many generations of dead stars is necessary before life can begin at all, then it looks to me like the odds are not at all good for intelligent life of any sort to exist right now on any random planet we may study. And, unfortunately, if they do exist, we will never meet them. If there is an incredibly advanced civilization somewhere within 100 light years that can actually detect those first radio signals, then they just received our first messages. If they do respond, we won’t get the answer for another century or two!

For example, take a look at this time line of life on earth at a linear scale. If a hypothetical space traveler should somehow arrive on the 3rd rock from our Sun at a random moment in time over the past 4.5 billion years, then that’s like tossing a dart at this graph while blindfolded, and seeing where it lands. Notice the kind of organisms dominating during most of the past 4 billion years! The chances that they would happen to arrive here in the past few centuries or so, when we humans began to really understand science, are vanishingly small!

https://slideplayer.com/slide/13671957/

EDIT:

My original title began with “Space Travel is Impossible” — which is obviously false, because it is an incontrovertible fact of history that a handful of American astronauts, at enormous expense, did in fact land on the Moon and return. I remember the event well; I was working in a factory in Waltham, Mass that summer as part of the SDS Summer Work-In.

I should have written, “Space Travel to Exoplanets Is Impossible”.

But you could make the case that traveling to the Moon is barely even space travel! The distance to the moon is less than the total mileage on my last two automobiles (a Subaru Forester and a Toyota Prius) added together. Or, at the speed of light, the Moon is about 1.5 light-seconds away, the Sun about 8 light-minutes, Jupiter 34 light-minutes, and Saturn is about 85 light minutes this month. But the very nearest star-planet system to us is over four YEARS away, and the distances to the vast majority of exoplanets are measured in light-decades, light-centuries, or light-millennia.

I remember the Space Race! Both the USA and the Soviets poured incredible sums of cash, labor, raw materials, and brain power into that race, while, frankly, millions of people around the world starved or were killed in proxy wars between those two powers, representing two ideological and political opposing blocks. The incredibly expensive and dangerous race to win global prestige by being the first power bloc to reach the various goals has, so far, at its apogee, carted a handful of men to the near side of our Moon, less than two light-seconds away! And some people think we can easily travel to exoplanets that are light-decades or light-centuries away!

Hah!

26 Thursday Oct 2023

Posted in astronomy, Optics, science, Telescope Making

For many years now, I have been trying and (mostly) failing at using some sort of digital camera when testing the optics of the mirrors we fabricate and evaluate at the ATM workshop at the Chevy Chase Community Center here in DC.

I can now report that there finally is some useful and non-vignetted light at the end of the testing tunnel!

I used an old Canon FD film camera lens (FL=28 mm) that I got about 40 years ago and haven’t used in several decades to get a bunch of really nice knife-edge images of a 16″ Meade mirror, located on a stage that can be moved forward and back in whatever steps I like by a smartphone app and a stepper motor setup that Alan Tarica and Pratik Tambe designed and put together.

Just now, I finally figured out how to use IrfanView to take one of the images, flip it left-to-right (that is, across the y-axis) and superimpose one onto the other with 50% transparency. A bright ring appeared, which shows the circular ring or zone where the light from our LED, located just under the camera lens, goes out to the mirror and bounces directly back to the lens and is captured by the sensor as a bright ring.

I then captured and pasted that image into Geometer’s Sketchpad, which I used to draw and measure the radii of two circles, centered at the doughnut marking the center of the mirror. This is a somewhat crude measurement of the radii, but it appears that this zone is is at 83% of the diameter (or radius) of the original disk, which is 16 inches across.

Now I just need to do the same thing for all of the other images, and then correlate the radii of the bright zones with the longitudinal (z-axis) motion of the camera and stand, and I will know how close this mirror is to a perfect paraboloid.

There is an app that supposedly does this for you, called Foucault Unmasked, but it doesn’t seem to work well at all. As you can see from these images, FU is unable to find zones that are symmetrically placed on either side of the center of the mirror. I don’t know what algorithm FU uses, but it sure is f***ed up.

Thanks a lot to Tom Crone, Gert Gottschalk, Pratik Tambe, Alan Tarica, and Alin Tolea for their help and suggestions!

22 Thursday Jun 2023

Posted in astronomy, flat, History, optical flat, Optics, Telescope Making

Tags

Algebra, dobsonian, foucault, geometry, Leon Foucault, Optics, parabola, paraboloid, Telescope, testing

Several people have helped me with this applied geometry problem, but the person who actually took the time to check my steps and point out my error was an amazing 7th grade math student I know.

It involves optical testing for the making of telescope mirrors, which is something I find fascinating, as you may have guessed. Towards the end of this very long post, you can see the corrections, if you like.

Optics themselves are amazingly mysterious. Is light a wave, or a particle, or both? Why can nothing go faster than light? We forget that humans have only very recently discovered and made use of the vast majority of the electromagnetic spectrum that is invisible to our eyes.

But enough on that. At the telescope-making workshop here in DC, I want folks to be able to make the best ordinary, parabolized, and coated mirrors possible with the least amount of hassle possible and at the lowest possible cost. Purchasing high-precision, very expensive commercial interferometers to measure the surface of the mirror is out of the question, but it turns out that very inexpensive methods have been developed for doing that – at least on Newtonian telescopes.

Tom Crone, a friend of mine who is also a fellow amateur astronomer and telescope maker, wondered how on earth we can report mirror profiles as being within a few tens of nanometers of a perfect paraboloid with such simple devices as a classic Foucault knife-edge test.

He told me his computations suggested to him that the best we could do is get it to within a few tenths of a millimeter at best, which is four orders of magnitude less precise!

I assured him that there was something in the Foucault test which produced this ten-thousand-fold increase in accuracy, but allowed that I had never tried to do the complete calculation myself. I do not recall the exact words of our several short conversations on this, but I felt that I needed to accept this as a challenge.

When I did the calculations which follow, I found, to my surprise, that one of the formulas I had been taught and had read about in many telescope-making manuals, was actually not exact, and that the one I had been told was inherently less accurate, was, in fact, perfectly correct! Alan Tarica sent me an article from 1902 supposedly explaining the derivation of a nice Foucault formula, but the author skipped a few bunch of important steps, and I don’t get anything like his results. it took me a lot of work, and help from this rising 8th grader, to find and fix my algebra errors. I now agree with the results of the author , T.H.Hussey.

I am embarrassed glad to say that even after several weeks of pretty hard work, an exact, correct formula for one of the commonly used methods for measuring ‘longitudinal aberration’ still eludes me. was pointed out to me by a student who took the time to Let’s see if anybody can follow my work and helped me out on the second method.

But first, a little background information.

Isaac Newton and Leon Foucault were right: a parabolic mirror is the easiest and cheapest way to make a high-quality telescope.

If you build or buy a Newtonian scope, especially on an easy-to-build Dobsonian mount, you will get the most high-quality photons for the money and effort spent, if you compare this type with any other type of optics at the same diameter. (Optical designs like 8-inch triplet apochromats or Ritchey-Chrétiens, or Maksutovs, or modern Schmidt-Cassegrains can cost many thousands of dollars, versus a few hundred at most for a decent 8″ diameter Newtonian).

With a Newtonian, you don’t need special types of optical glass whose indices of refraction and dispersion, and even chemical composition, must be known to many decimal places. The glass can even have bubbles and striations, or not even be transparent at all! Any telescope that only has mirrors, like a Newtonian, will have no chromatic aberration (ie, you don’t see rainbows around bright stars) because there is no refraction – except for inside your eyepieces and in your eyeball. All wavelengths of light reflect exactly the same –but they bend (refract) through glass or other materials at different angles depending on the wavelength.

Another advantage for Newtonians: you don’t need to grind and polish the radii of curvature of your two or three pieces of exotic glass to exceedingly strict tolerances. As long as you end up with a nice parabolic figure, it really doesn’t matter if your focal length ends up being a few centimeters or inches longer or shorter than you had originally planned. Also: there is only one curved mirror surface and one flat one, so you don’t need to make certain that the four or more optical axes of your mirrors and/or lenses are all perfectly parallel and perfectly concentric. Good collimation of the primary and secondary mirrors to the eyepiece helps with any scope, but it’s not nearly as critical in a Newtonian, and getting them to line up if they get knocked out of whack is also much easier to perform.

With a Newtonian, you only need to get one surface correct. That surface needs to be a paraboloid, not a section of a sphere. (Some telescopes require elliptical surfaces, or hyperbolic or spherical ones, or even more exotic geometries. A perfect sphere is the easiest surface to make, by the way.)

In the 1850’s, Leon Foucault showed how to ‘figure’ a curved piece of glass into a sufficiently perfect paraboloid and then to cover it with a thin, removable layer of extremely reflective silver. The methods that telescope makers use today to make sure that the surface is indeed a paraboloid are variations and improvements on Foucault’s methods, which you can read for yourself in my translation.

It turns out that the parabolic shape does need to be very, very accurate. In fact, over the entire surface of the mirror, other than scratches and particles of dust, there should be no areas that differ from each other and from the prescribed geometric shape by more than about one-tenth of a wavelength of green light (which I will call lambda for short), because otherwise, instead of a sharp image, you just receive a blur, because the high points on the sine waves of the light coming to you would tend to get canceled out by the low points.

Huh?

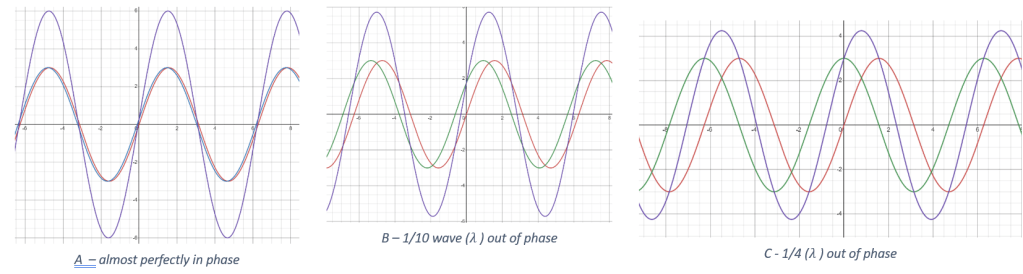

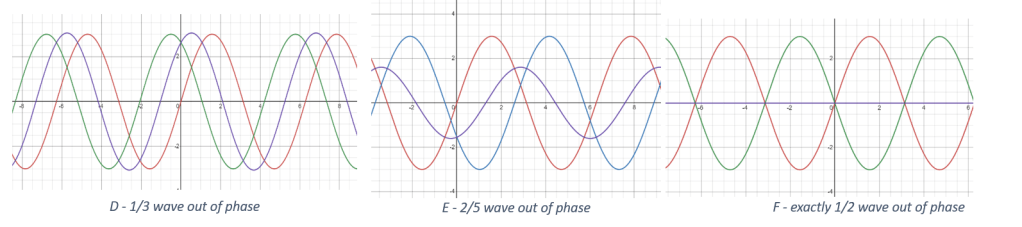

Let me try to explain. In my illustrations below, I draw two sine waves (one red, one green) that have the same exact frequency and wavelength (namely, two times pi) and the same amplitude, namely 3. They are almost perfectly in phase. Their sum is the dark blue wave. In diagram A, notice that the dark blue wave has an amplitude of six – twice as much as either the red or green sine wave. This means the blue and green waves added constructively.

Next, in diagram B, I draw the red and green waves being out of phase by one-tenth of a wave (0.10 lambda) , and then in diagram C they are ‘off’ by ¼ of a wave (0.25 lambda). You will notice that in the diagrams B and C, the dark blue wave (the sum of the other two) isn’t as tall as it was in diagram A, but it’s still taller than either the red or green one.

One-quarter wave ‘off’ is considered the maximum amount of offset allowed. Here is what happens if the amount of offset gets larger than 1/4:

In diagram D, the red and green curves differ by 1/3 of a wave (~0.33 lambda), and you notice that the blue wave (which is the sum of the other two) is exactly as tall as the red and green waves, which is not good.

Diagram E shows what happens is what happens when the waves are 2/5 (0.40 lambda) out of phase – the blue curve, the sum of the other two, now has a smaller amplitude than its components!

And finally, if the two curves differ by ½ of a wave (0.5 lambda) as in diagram F, then the green and red sine curves cancel out completely – the dark blue curve has become the x-axis, which means that you would only see a blur instead of a star or a planet. This is known as destructive interference, and it’s not what you want in your telescope!

But how on earth do we achieve such accuracy — one-tenth of the wavelength of visible light (λ/10) over an entire surface? And if we do, what does it mean, physically? And why one-tenth λ on the surface of the mirror, when ¼ λ looked pretty decent? For that last question, the reason is that when light bounces off a mirror, any deviations are multiplied by 2.

So lambda – about 55 nanometers or 5.5×10^(-8) m- is the maximum allowable depth or height of a bump or a hollow across the entire width of the mirror.

That’s really small!

How small?

Really insanely small.

Let’s try to visualize this by enlarging the mirror. At our mirror shop, we generally help folks work on mirrors whose diameters are anywhere from 11 cm (4 ¼ inches) to 45 cm (18 inches) across. Suppose we could magically enlarge an 8” (20 cm) mirror and blow it up so that it has the same diameter as the original 10-mile (16 km) square surveyed in 1790 by the Ellicott brothers and Benjamin Banneker for the 1790 Federal City. (If you didn’t know, the part on the eastern bank of the Potomac became the District of Columbia, and the part on the western bank was given back to Virginia back in 1847. That explains why Washington DC is no longer shaped like a nice rhombus/diamond/square.)

So imagine a whole lot of earth-moving equipment making a large parabolic dish where DC used to be, a bit like the Arecibo radio telescope, but about 50 times the diameter, and with a parabolic shape, unlike the spherical one that Arecibo was built with.

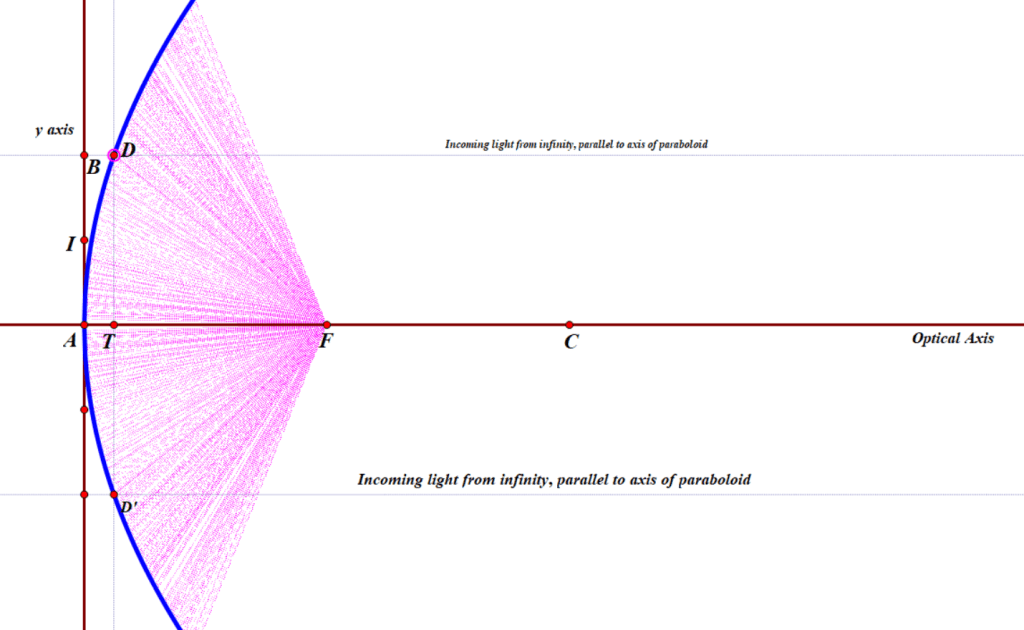

(Technical detail: since Arecibo was so big, there was no way to physically steer it around at desired targets in the sky. Since they couldn’t steer it, then a parabolic mirror would be useless except for directly overhead. However, a spherical mirror does NOT have a single focal point. So the scope has a movable antenna (or ‘horn’) which can move around to a variety of more-or-less focal points, which enabled them to aim the whole device a bit off to the side, so they can ‘track’ an object for about 40 minutes, which means that it can aim at targets around 5 degrees in any direction from directly overhead, but the resolution was probably not as good as it would have been if it had a fully steerable, parabolic dish. See the following diagrams comparing focal locations for spherical mirrors vs parabolic mirrors. Note that the spherical mirror has a wide range of focal locations, but the parabolic mirror has exactly one focal point.)

I’ll use the metric system because the math is easier. In enlarging a 20 cm (or 0.20 m) mirror all the way to 16 km (which is 16 000 m), one is multiplying 80,000. So if we take the 5.5×10-8 m accuracy and multiply it by eighty thousand you get 44 x 10-4 m, which means 4.4 millimeters. So, if our imaginary, ginormous 16-kilometer-wide dish was as accurate, to scale, as any ordinary home-made or commercial Newtonian mirror, then none of the bumps or valleys would be more than 4.4 millimeters too deep or too high. For comparison, an ordinary pencil is about 6.8 millimeters thick.

Wow!

So that’s the claim, but now let’s verify this mathematically.

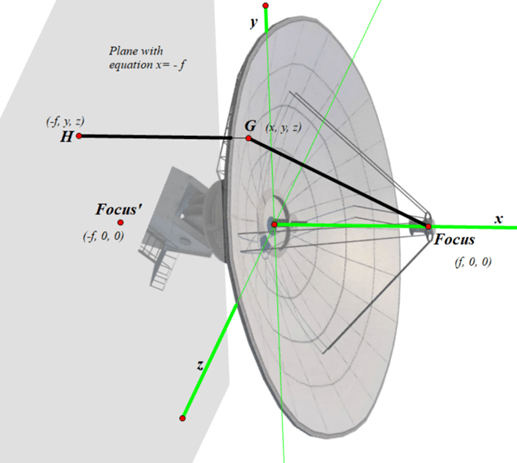

I claim that such a 3-dimensional paraboloid, like the radio dish in the picture below, can be represented by the equation

where f represents the focal length. (For simplicity, I have put the vertex of the paraboloid at the origin, which I have called A. I have decided to make the x-axis (green, pointing to our right) be the optical and geometric axis of the mirror. The positive z-axis (also green) is pointed towards our lower left, and the y-axis (again, green) is the vertical one. The focal point is somewhere on the x-axis, near the detector; let’s pretend it’s at the red dot that I labeled as Focus.)

You may be wondering where that immediately previous formula came from. Here is an explanation:

Let us define a paraboloid as the set (or locus) of all points in 3-D space that are equidistant from a given plane and a given focal point, whose coordinates I will arbitrarily call (f, 0, 0). (When deciding on a mirror or radio dish or reflector on a searchlight, you can make the focal length anything you want.)

To make it simple, the plane in question will be on the opposite side of the origin; its equation is x = -f. We will pick some random point G anywhere on the surface of the parabolic dish antenna and call its coordinates (x, y, z). We will see what equation these conditions create. We then drop a perpendicular from G towards the plane with equation x = -f. Where this perpendicular hits the plane, we will call point H, whose coordinates are (-f, y, z). We need for distance GH (from the point to the plane) to equal distance from G to the Focus. Distance GH is easy: it’s just f + x. To find distance between G and Focus, I will use the 3-D distance formula:

Which, after substituting, becomes

To get rid of the radical sign, I will equate those two quantities, because FG = GH, omit the zeroes, and square both sides. I then get

Multiplying out both sides, we get

Canceling equal stuff on both sides, I get

Adding 2fx to both sides, and dividing both sides by 4f, I then get

However, 3 dimensions is harder than 2 dimensions, and two dimensions will work just fine for right now. Let us just consider a slice through this paraboloid via the x-y plane, as you see below: a 2-dimensional cross-section of the 3-dimensional paraboloid, sliced through the vertex of the paraboloid, which you recall is at the origin. We can ignore the z values, because they will all be zero, so the equation for the blue parabola is

or, if you solve it for y, you get

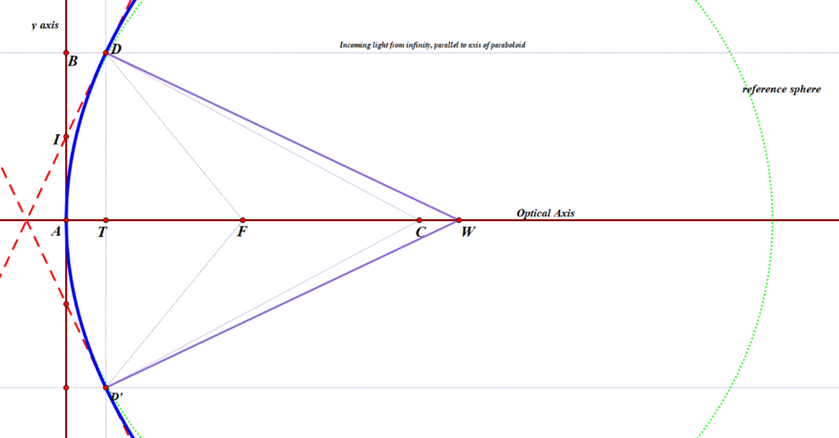

There is a circle with almost the same curvature as the paraboloid; its center, labeled CoC (for ‘Center of Curvature’) is exactly twice as far from the origin as the focal point. You can just barely see a green dotted curve representing that circle, towards the top of the diagram, just to the right of the blue paraboloid. center of the circle (and sphere). Its radius is 2f, which obviously depends on the location of the Focus.

D is a random point on that parabola, much like point G was earlier, and D’ being precisely on the opposite side of the optical axis. The great thing about parabolic mirrors is that every single incoming light ray coming into the paraboloid that is parallel to the axis will reflect towards the Focus, as we saw earlier. Or else, if you want to make a lamp or searchlight, and you place a light source at the focus, then all of the light that comes from it that bounces off of the mirror will be reflected out in a parallel beam that does not spread out.

In my diagram, you can see a very thin line, parallel to the x-axis, coming in from a distant star (meaning, effectively at infinity), bouncing off the parabola, and then hitting the Focus.

I also drew two red, dashed lines that are tangent to the paraboloid at point D and D’. I am calling the y-coordinate of point D as h (D has y-coordinate -h)and the x-coordinate of either one is

I used basic calculus to work out the slope of the red, dashed tangent line ID. (Quick reminder, if you forgot: in the very first part of most calculus classes, students learn that the derivative, or slope, of any function such as this:

is given by this:

So for the parabola with equation

the slope can be found for any value of x by plugging that value into the equation

Since

the exponent b is one-half. Therefore, the slope is going to be

which simplifies to

Now we need to plug in the x coordinate of point D, namely

we then get that the slope is

To find the equation of the tangent line, I used the point-slope formula y – y1=m(x – x1). ; plugging in my known values, I got the result

To find where this hits the y-axis, I substituted 0 for x, and got the result that the tangent line hits the y-axis at the point (0, h/2) — which I labeled as I — or one-half of the distance from the vertex (or origin) to the ‘height’ of the zone, or ring, being measured.

Line DW is constructed to be perpendicular to that tangent, so any beam of light coming from W that hits the parabola at point D will be reflected back upon itself. Perpendicular lines have slopes equal to the negative reciprocal of the other. Since the tangent has slope 2f/h, then line DW has slope -h/(2f).

Plugging in the known values into the point-slope formula, the equation for DW is therefore

Here, I am interested in the value of x when y = 0. Substituting, re-arranging, and solving for x, I get

Recall that point C is precisely 2f units from the origin, which means that the perpendicular line DW hits the x axis at a point that is the same distance from the center of curvature CoC as the point D is from the y-axis!

Or, in other words, CW = AT = DE. This means: if you are testing a parabolic mirror with a moving light source at point W, then a beam of light from W that is aimed at point D on the paraboloid will come right back to W, and the longitudinal readings of distance will follow the rule h2/(4f), where h is the radius of the zone, or ring, that you are measuring. Other locations on the mirror which do not lie in that ring will not have that property. This then is the derivation of the formula I was taught over 30 years ago by Jerry Schnall, and found in many books on telescope making – namely that for a moving light source, since R=2f,

where LA means ‘longitudinal aberration and the capital R is the radius of curvature of the mirror, or twice the focal length. So that’s exactly the same as what I computed.

HOWEVER, this formula [ LA=h^2/(2R) ] does not work at all if your light source is fixed at point C, the center of curvature of the green, reference sphere. In the old days, before the invention of LEDs, the light sources were fairly large and rather hot, so it was easier to make them stationary, and the user would move the knife-edge back and forth, but not the light source. The formula I was given for this arrangement by my mentor Jerry Schnall, and which is also given in numerous sources on telescope making was this:

that is, exactly twice as much as for a moving light source. I discovered to my surprise that this is not correct, but it took me a while to figure this out. I originally wrote the following:

But now I can confirm this, thanks in part to two of my very mathematically inclined 8th grade geometry students. Here goes, as corrected:

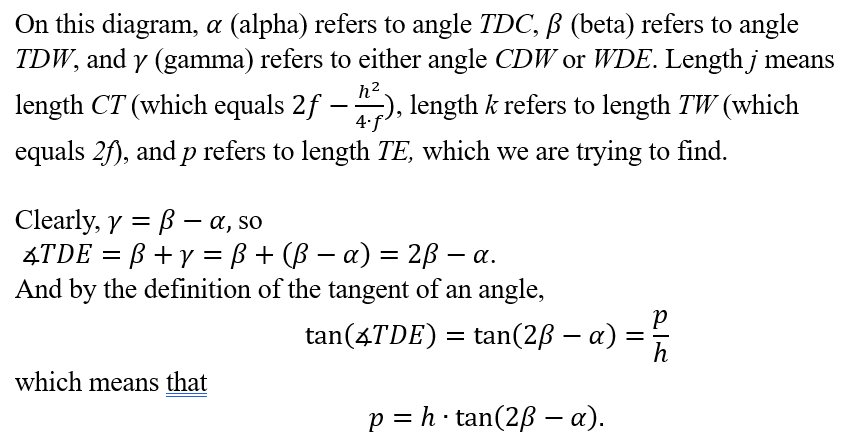

If one is using a fixed light source located at the center of curvature C, and a moving knife-edge, located at point E, the the rays of light that hit the same point D will NOT bounce straight back, because they don’t hit the tangent line at precisely 90 degrees. Instead, the angle of incidence CDW will equal the angle of reflection, namely WDE. I used Geometer’s sketchpad to construct line DE by asking the software to reflect line CD over the line DW.

However, calculating an algebraic expression for the x-coordinate of point E was surprisingly complicated. See if you can follow along!

To find the x-coordinate of E, I will employ the tangent of angle TDE.

To make the computations easier, I will draw a couple of simplified diagrams that keep the essentials.

I also tried other approaches, and also got answers that made no sense. It looks like the formula in the 1902 article is correct, but I have not been able to confirm it.

I suspect I made a very stupid and obvious algebra mistake that anybody who has made it through pre-calculus can easily find and point out to me, but I have had no luck in finding it so far. I would love for someone did to point it out to me.

Thanks.

But this still does not answer Tom’s question!

02 Tuesday May 2023

Tags

ALAN, artificial light at night, extinction, full cutoff lighting, insect collapse, insects, light pollution

People have long wondered why flying insects can be seen spiraling around light sources at night. Among other suggestions was that the critters were used to navigating by the Moon, and got confused, or that they were seeking heat.

An ingenious new study shows that the navigation idea is not completely wrong, but the insects instead use sky glow, even at night, as a major clue for how to orient themselves: by keeping their dorsal (back) to a point or diffuse light source, for millions of years, then they would keep their legs pointed down and they would fly the way they want.

However, these researchers found that if they placed a light bulb in roughly the center of an otherwise darkened, enclosed space inside a tent with flying insects, then most (but not all) species of nocturnal insects flying above or to the side of the light tended to orient their bodies so that their dorsal side was towards the light— so that they were flying sideways or upside down! Thus disoriented, they would flitter around, confused as to which way was up.

This also explains why it is so easy to catch nocturnal flying insects by shining a bright light onto a sheet or blanket laid on the ground: convinced by hundreds of millions of years that “light = up”, a large fraction of the critters fly **upside down** towards the lighted surface and careen onto it, out of control.

Caution: This study has not yet been replicated or peer-reviewed, but if it holds up, then it unveils a very simple and inexpensive fix for both ever-worsening light pollution and the collapse of our global insect populations: simply put shielding around ALL exterior light fixtures at night, so that NO light is emitted either upwards or sideways. (This is known as a Full cut-off (FCO) lighting.)

Larger animals like birds, reptiles, and mammals can simply use gravity to tell them which way is up. Insects, by contrast, are apparently so small that the air itself acts like a viscous medium, and tends to overpower the cues from gravity, much like scuba divers can get confused as to which way is up — unless they follow cues like air bubbles and where the diffused light from the surface comes from.

“The largest flying insects, such as dragonflies and butterflies, can leverage passive stability to help stay upright 30, 31. However, the small size of most insects means they travel with a lower ratio of inertial to viscous forces (Reynolds number) compared with larger fliers32. Consequently, smaller insects, such as flies, cannot glide or use passive stability, yet must still rapidly correct for undesired rotations33. Multiple visual and mechanosensory mechanisms contribute to the measurement and correction of undesired rotations, but most measure rotational rate rather than absolute attitude 26, 28, 32, 34. In environments without artificial light, the brightest portion of the visual environment offers a reliable cue to an insect’s current attitude.”

“Inversion of the insect’s attitude (either through roll or pitch) occurred when the insect flew directly over a light source (Fig. 1 c & Supp. Video 3), resulting in a steep dive to the ground. Once below the light, insects frequently righted themselves, only to climb above the light and invert once more. During these flights, the insects consistently directed their dorsal axis towards the light source, even if this prevented sustained flight and led to a crash.”

The researchers report that certain types of insects did **not** appear to get confused by lights at night: Oleander Hawkmoths (Daphnis nerii) and fruit flies (drosophila).

Here is the link to the preprint:

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.04.11.536486v1.full