ESSENTIAL STEPS FOR MAKING YOUR OWN TELESCOPE

By Guy Brandenburg

[Guy is the main telescope-making instructor at the amateur telescope-making (ATM) workshop sponsored by the National Capital Astronomers (NCA). This workshop is currently housed in the basement the Chevy Chase Community Center (CCCC) at 5601 Connecticut Avenue, NW, WDC 20015.

[This guide is based on what Guy has gleaned by reading a variety of books on telescope making, as well as instruction by Jerry Schnall (his predecessor in this workshop), watching demonstrations at Stellafane, his own participation in two Delmarva Mirror-Making Marathons, visits from other ATMers to our workshop (including by John Dobson), a tour of a commercial optical factory near Bel-Air MD, a couple of weeks in residence at Mount Wilson (CA) and a few visits to the Chabot telescope-making workshop in Oakland, CA. He has tried to steal good ideas from all of them, incorporating what he has taught for years in his math classes in DC public schools. He tries not to insert too many bad ideas of his own.

[Our current Telescope Making, Modification and Maintenance Workshop (TMMW) meets on Tuesdays and Fridays except for snow and holidays, from 6:00 to about 8:30 pm. You can contact Guy at gfbrandenburg@gmail.com. Since we have dangerous power and hand tools in our workshop, all visitors must sign a release-of-liability form upon arrival and must also register with the DC Department of Parks and Recreation,

[Guy is also the current president of NCA, which was founded in 1937 in DC by a group of professional and amateur astronomers. Famous astronomers Vera Rubin and Nancy Grace Roman were members. Records show that NCA has continuously sponsored this telescope making workshop, in various locations around DC and suburbs, since World War 2.]

{It is certainly true that you can purchase used telescopes for a fraction of their original price — but what if the telescope you bought doesn’t actually work? You would need to learn to fix it yourself, because repair bills can be quite high, negating any cost savings. If the scope involves electronics that won’t work, the older the device, the less likely that it can be repaired or that anybody actually stocks replacement parts. All hope is not lost! You can replace a fried and non-replaceable commercial electronic drive with stepper motors and an Arduino using a free system called OnStep. However, be prepared to learn a lot about gear ratios, voltages, soldering, and IC boards. Kind of fun, but time-consuming! If you are local, we can help, at our workshop, for free.}

But, if you still want to make a telescope, then …

- Plan your project by looking at various home-made and commercial telescopes, either in person or in books or magazines or on-line. Star parties put on by local clubs often will have some home-made telescopes on the field, and their owners/makers will be delighted to tell you what worked well and what they would wish to modify one day. Decide what size and focal length you can afford to make and can actually manage to carry around in your car or your hands, or install somewhere permanently. A Newtonian reflector is by far the easiest type of telescope design to make yourself. If you keep at it and don’t drop the mirror on a hard floor, you are pretty much guaranteed success and a well-performing telescope. All of the other designs (refractors, cassegrains, catadioptrics, etc.) are much, much harder to make and can fail for reasons that are very hard to figure out. Larger-diameter scopes are more expensive, heavier, and take more time to make, but you can see more detail and dimmer objects, too.

- Costs: If you are thrifty and crafty, you can definitely make a telescope of a given size for less money than one you purchase, but if you insist on the finest and most expensive components (exotic wood, for example), you can end up spending much more. Fifty years ago, the only way that the average person could afford to own a telescope was if they made it themselves; commercial 6-inch scopes sold in the 1950s for prices that are equivalent to about $2,000 in today’s money. Today, a six-inch commercial telescope and mount costs much less than that, and the prices of Pyrex-equivalent mirror blanks have recently tripled. A recent study in Sky & Telescope found that the biggest potential savings are for large telescopes, but a lot depends on one’s ability to scrounge and find inexpensive, but good-quality, components.

B. Time: It’s not possible to say exactly how long any project will take. However, I always find that everything that I make, takes longer than I originally estimate, which is known as Hofstadter’s Law. When I made my first telescope, a 6” f/8, I kept notes on how much time I spent on grinding, polishing and figuring, and later added that all up: 30 hours. My second telescope, an 8” f/6, took me 40 hours. But keep in mind, those totals only count the time I spent actually pushing glass, not the time planning things, thinking about things, discussing the project, taking Ronchi and Foucault measurements, setting up the work, and cleaning up after a grit. They also did not include any of the time I spent on making the tubes and mounts or aluminizing the mirrors or learning how to use the telescopes in the first place. Obviously, you might take less time than me, or longer.

C. Longer focal length for a given diameter means sharper images of stars and planets, and usually an easier job of grinding and figuring, and they work well with less-expensive eyepieces, and the scope will work even if not perfectly collimated (aligned internally), and you won’t have problems with coma. However, it also means dimmer images with narrower fields of view, and objects will remain visible for shorter lengths of time, requiring constant adjustment; also the scope will be longer, heavier, and harder to maneuver. A focal ratio of 6 is considered by many ATMers to be an intermediate one.

D. A shorter focal length for a given diameter means brighter images, a wider field of view, and a shorter, lighter telescope that is easy to carry around. However, the figuring process will be more difficult, collimation will be more critical, and coma will be a problem at the edges of your field of view. You may need to use additional tests to verify that your mirror is in fact well-figured.

E. The difficulty, cost, weight, and amount of time needed to make a scope is roughly proportional to the cube of the diameter, which means that a scope with a 12-inch diameter mirror will be about 8 times harder, heavier, and more expensive than a 6 inch diameter telescope. On the other hand, its light-gathering power is proportional to the square of the diameter, so the 12-inch mirror will gather four times the amount of light than a 6-inch mirror, which in practice means that you will see stars and other objects a magnitude or two fainter with the larger scopes.

F. As you can see, in astronomy, there are trade-offs. There is no car, no boat, no garment, no athlete, and no telescope that is BEST for ALL purposes. For example, a scope that is really good at providing a wide-field image of the Pleiades won’t do well at imaging the bands and festoons on Jupiter. Just setting up a huge scope 20” or more in diameter is a major undertaking and probably requires a step-ladder, whereas a 6” Dob can be set up and ready to go in about a minute by a sixth-grader. A large Dob is going to do its best work at a dark-sky location like the Rockies or parts of West Virginia. A computerized go-to scope, which you are probably not going to be able to build yourself unless you have some amazing skills in machining, computer programming, and electrical engineering, can work anywhere. Your goal should be to build a telescope that will be used!

G. Rather important: a home-made Dobsonian-mounted Newtonian reflector is not really suitable for astrophotography. For that, you will need a very expensive equatorial mount as well as a digital camera of some sort (DSLR or CCD or dedicated web-cam) and, usually, a computer and a power supply. A “Dob” is GREAT for optical viewing with your eyes, and you don’t have to spend the entire night doing polar alignment, taking flats and darks and multiple guided exposures of the same object for hours on end with an expensive DSLR or CCD camera or dedicated web-cam; nor do you have to spend hours and hours learning how to digitally process all those digital images. Instead, you LOOK with your eyes, and you can look at dozens of different objects in a night, without fussing with electronic gadgets…

H. You will need to decide on the materials for your mirror: plate glass (relatively cheap but usually no more than ¾” thick), Pyrex or its generic equivalents, or a relatively exotic material such as ‘fused silica’ (i.e. quartz) or a really exotic material like Zerodur, Cer-Vit, or BVC. For several decades, ATMers used full-thickness Pyrex mirror blanks produced in massive amounts by Corning Glass. They were relatively inexpensive, durable, and had low thermal coefficients of expansion. Unfortunately, Corning has stopped making Pyrex, and the generic replacements known as Borofloat and other trade names are now made overseas in considerably smaller batches, so the price for a full-thickness borosilicate crown glass equivalent to Pyrex has tripled or quadrupled. It turns out that modern float glass (also called plate glass) works quite well for making telescopes, unlike the wavy window-pane glass of 80 years ago. The term “float” means that the glass is made in a continuous process and is annealed and manufactured to be extremely flat and homogeneous by, yes, floating it on a bed of pure molten tin. You do have to be more careful about preventing astigmatism, and must cool the glass down to ambient room temperature in a bath of cool water whose temperature you have measured, but many excellent mirrors have been made using ¾”-thick plate glass cut into disks by the water-jet method at a local glass fabricator.

I. Instead of making your own mirror, you could buy a used or new one that someone else made. There are generally several used primary mirrors for sale at any given time, of various sizes and prices, at websites like eBay, Cloudy Nights Classified, or Astromart. Astromart has the widest selection, but you have to pay a fee (about $10-$20 per year) to post or respond to ads. Cloudy Nights has a lot of forums where people express their opinions on subjects astronomical, and many of them are probably correct. (Definitely worth reading in any case!) Some of the scopes you can find are real bargains, but you don’t know what the quality is unless you or someone you trust tests it. Here at the NCA ATM workshop, we generally have some mirrors of various sizes that were either made by one of us, or which were donated to us, or which we bought through one of those online sources.

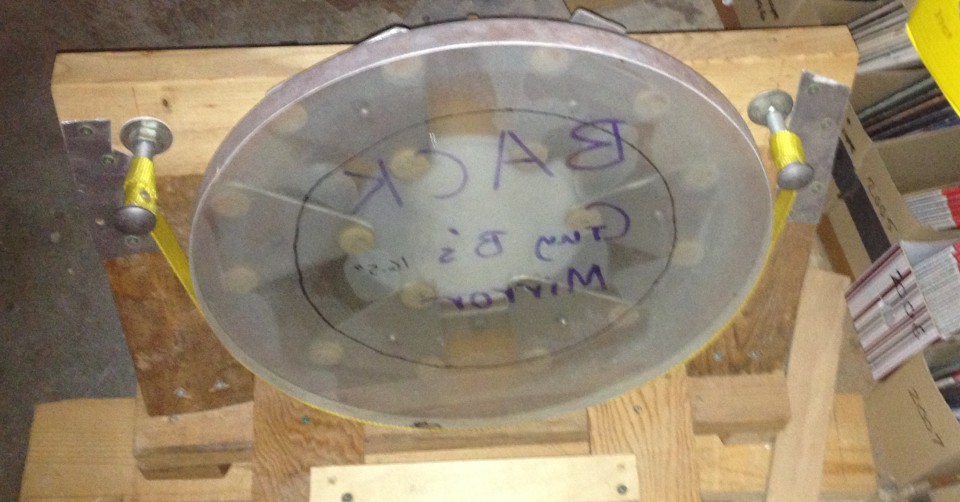

J. Record-keeping: you will be engaging in a scientific project, so you will need to do what scientists do: keep records of what you do. Write down what grit size you are on, what sort of stroke you are using, how long you spent on the various steps, and how you overcame the various problems that arose. If possible, take photographs of your work (especially of the ronchigrams during the figuring process). Also make plenty of diagrams and sketches and calculations, and label them, too! Your notes will let you know what works and what doesn’t, and will save you a tremendous amount of time. At the CCCC, we have a file cabinet and hanging file folders in which you can keep your notes.

K. If you have decided to make your own mirror for your own telescope, then there are four major steps: Rough grinding or “hogging out”; medium and fine grinding; polishing; and figuring. The hardest part is the figuring, but fortunately by the time you get there, you will have learned a lot about how to treat the glass. Let’s examine all four steps, in my next post. ==>