I help run the amateur telescope-making workshop at the Chevy Chase Community Center in Washington, DC, sponsored and under the auspices of the National Capital Astronomers. Both the NCA and its ATM group have been on-going since the 1930’s, well before I was born. In our ATM group, have the somewhat esoteric thrill of manufacturing incredibly accurate scientific devices (telescopes), from scratch, with not much more than our bare hands and a few tools. And then we go and use them to observe the incredible universe we come from.

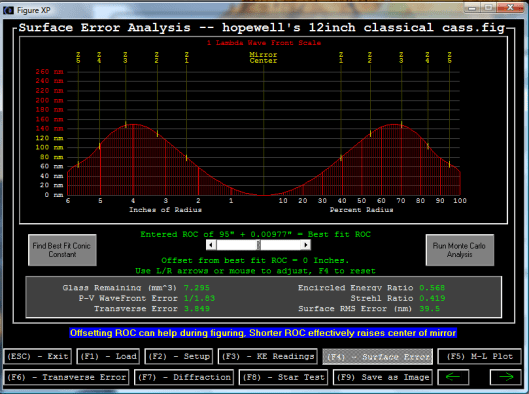

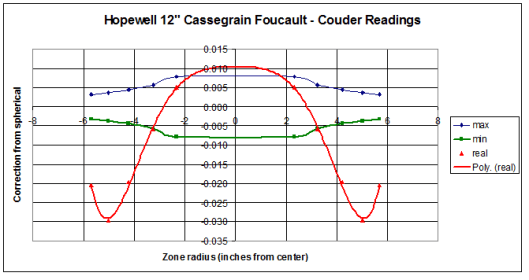

Since these telescope mirrors are required to be insanely accurate, we need extremely high-precision ways of testing them. However, we don’t have the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars needed to purchase something like a professional Zygo Interferometer, so we use much cheaper ways of testing our mirror surfaces.

Some of those methods are associated with the names Foucault, Couder, Bath, Ronchi, Ross, Everest, and Mobsby, or are described with words like “knife-edge”, “double-pass” and “wire”. They all require some relatively simple apparatus and skill and practice in measurement and observation.

We are of the opinion that no one single test should be trusted: it’s easy to make some sort of error. (I’ve made plenty.) You may perhaps recall the disaster that happened when the Hubble Space Telescope mirror passed one test with flying colors, and other tests that weren’t so good were ignored. When the HST finally flew in orbit, it was discovered that the mirror was seriously messed up: the test that was trusted was flawed, so the mirror was also flawed.

We don’t want to do that. So, at a minimum, we do the Ronchi and Foucault/Couder knife-edge tests before we say that a mirror is ready to coat.

But the ultimate test of an entire telescope is the star test.

In principle, all you need for that is a steady star, your telescope, a short-focal-length eyepiece, and a copy of Richard Suiter’s book on star-testing optical telescopes.

Unfortunately, around here, it’s often cloudy at night, and if it’s clear, it might be windy, and around the CCCC building there are lots of lights — all of which make star-testing a scope on the two evenings a week that we are open, virtually impossible. We aren’t open in the daytime, and even if we were, I don’t see any ceramic insulators on any telephone poles that are both small enough and far enough away to use as artificial stars in the manner that Suiter describes. (There are a few radio towers visible, but I doubt that their owners would let us climb up one of them and hang up a Christmas tree ornament near the top!)

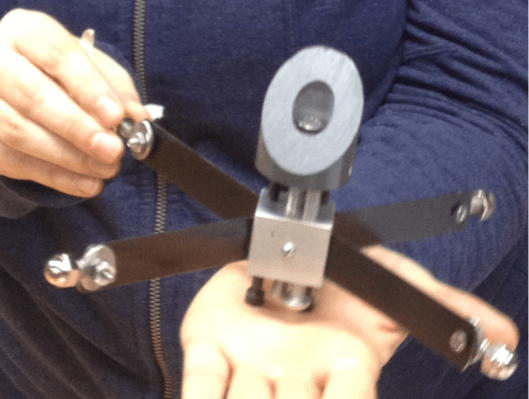

So, that means we need to make an artificial star.

I’ve been reading a few websites written by folks who have done just that, and it seems to be a bit easier than I thought. The key is to get a source of light that acts like a star at astronomical distances — but close enough that we can fit it inside the basement of the CCCC, probably not in the woodshop where we make the scopes, but more likely out in the hallway or in the large activity room next door, both of which are about 40 or 50 feet long.

So here are my preliminary calculations.

First off, it appears that the resolving power of a telescope equals the wavelength being used, divided by the diameter of the objective lens or mirror, both expressed in the same units. The result is in radians, which you can then turn into degrees, arc-minutes, arc-seconds, or whatever you like, but it’s perhaps easier to leave in radians. In any case, the larger the diameter, the tinier the angle that your telescope can resolve if it’s working properly.

I am going to use a 16-inch mirror diameter, or about 0.4 meters, as an example, and I will use green light at about 560 nanometers (560 x 10^-9 m) because that’s pretty close to the green mercury line we have in our monochromatic light box. I then get that the resolution is 1.4×10^-6 radians.

(We can convert that into arc-seconds by multiply that by 180 degrees per PI radians and by 60 arc-minutes per degree and by 60 arc-seconds per arc-minute; we then get about 0.289 arc-seconds. If we were to use an 8-inch mirror, the resolution would be half as good, meaning the object would need to be twice as big to be resolved, or about 0.578 arc-seconds.)

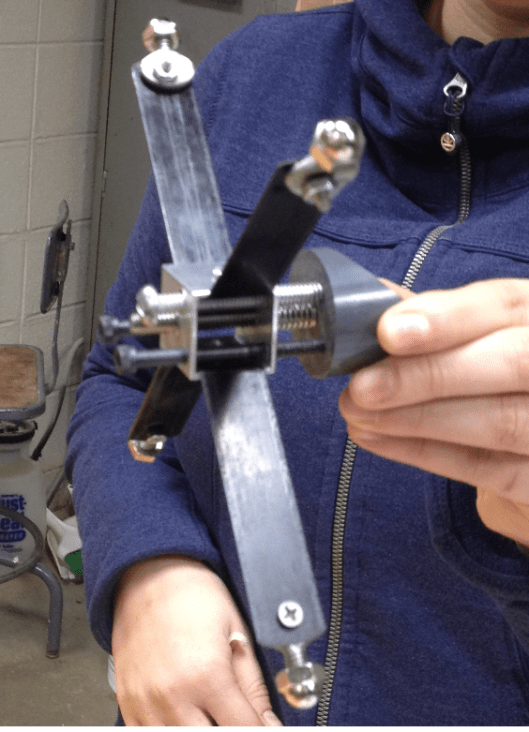

I read that one can make an artificial star by using an ordinary eyepiece and a small illuminated hole that is put some distance away from the eyepiece. The entire setup is aimed at the telescope, and then you have an artificial star. Here is the general idea:

Supposedly, the equations go as follows, with all of the dimensions in the same units. I think I will use millimeters.

We want to make it so that the size of the artificial star will be small enough to be below the limit of resolution of any telescope we are making. I am pretty sure that we can set things up so that there is 40 feet (13 meters) between our telescope rig and the table or tripod on which we sill set up this artificial star.

We want to make it so that the size of the artificial star will be small enough to be below the limit of resolution of any telescope we are making. I am pretty sure that we can set things up so that there is 40 feet (13 meters) between our telescope rig and the table or tripod on which we sill set up this artificial star.

I also know that I can find an eyepiece with a focal length of 12 mm that I’m willing to use for this purpose, and I also purchased some tiny little holes from “Hubble Optics” that are of the following sizes: 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 microns, or millionths of a meter. Those holes are TINY!!! So that takes care of H and F. I still need to figure out what SS should be.

A few lines ago, I found that for a 16-inch telescope, I need a resolution of about 1.4×10^-6 radians. The nice thing about radians is that if you want to find the length of the arc at a certain radius, you don’t need to do any conversions at all: the length of the arc is simply the angle (expressed in radians) times the length of the radius, as shown here:

So if our artificial star is going to be 13 meters away, and we know that the largest angle allowed is roughly 1.4×10^-6 radians, I just multiply and I get 1.82×10^-5 meters, or 1.82 x 10^-2 millimeters, or 18.2 microns.

Which means that I already have holes that are NOT small enough: the 150-micron holes are about 10 times too big at a distance of 13 meters, so my premature rejoicing of a few minutes ago, was, in fact, wrong. So, when I make the artificial star gizmo, I’ll need to figure out how to make the ‘star size’ to be roughly one-tenth the size of the holes in the Hubble Optics micro-hole flashlight.

Or, if I rearrange the equation with the L, H, F and SS, I get that L = H * F / SS. The only unknown is L, the distance between the hole and the eyepiece/lens. For H, I have several choices (50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 microns), SS is now known to be 18 microns or so (36 if I want to test an 8-incher), and I plan on using a 12.5 mm eyepiece. If I plug in the 150 micron hole, then I get that L needs to be about 104 millimeters, or only about 4 inches. Note that the longer L is, the smaller the artificial star becomes. Also, if I replace the 12.5 mm eyepiece with a shorter one, then the artificial star will become smaller; similarly, the smaller the Hubble Optics hole, the smaller the artificial star. This all sounds quite doable indeed.